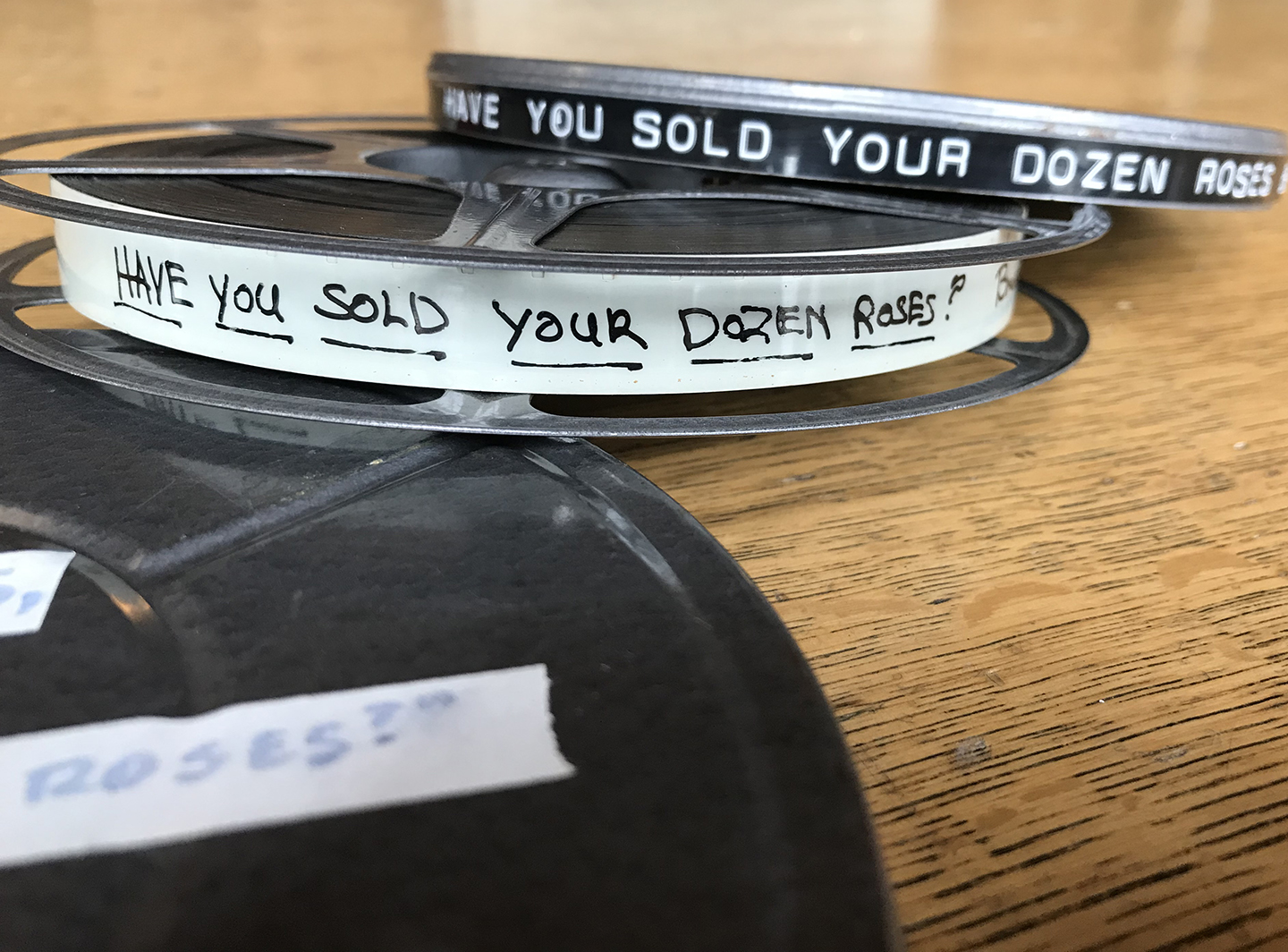

Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses?

Author

Nina Zurier

Decade

1950s

Tags

Filmmaking Poetry Music Trash

Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses?: How it was made.

In 1957, I was one of five students in the film class at the California School of Fine Arts, now the San Francisco Art Institute. It had long been taught by Robert Katz, whose excellent gifts lay more in film history and evaluation than in production.

Later that spring, he took a leave of absence and asked a former student, David Myers, to take over . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . which is to say, a morning came when Dave Myers—soon to become one of the great cinema verité cameramen of all times, famous for Woodstock, The Grateful Dead movie, and dozens of others—walked into the classroom and asked: “Is there anything to shoot with? Any cameras? Any film??”

We had two Bell & Howell 16mm cameras (one of the great wind-up cameras of all times) and about two dozen 100-foot rolls of black-and-white film, Plus-X and Tri-X. We put this and a couple of changing bags in my car, and Allen Willis and Dave (who had his own Bell & Howell) and I drove to Oakland in the rain to cancel complicated plans Bob had made to film blind children. When we were on the bridge, heading back to San Francisco, it was beginning to clear up, and Dave said, “Let’s go film the dump.” This struck us as better than a good idea, and shortly we were at the dump, loading cameras.

I think that this is where the magic began, because without a word between us, we all went in different directions and began filming. In fact, never once during the three trips we eventually made to that dump and the big one near 101 did we ever confer about what the goal was, or what we were doing. When it got near the end of class time, we simply stopped, and dropped the film off at Monaco Lab, on the way back to school. The following week we looked at the footage, thought “wow,” and went back to the dump. There was no discussion except raving over individual shots. You have to remember that there were two conscious/subconscious realities operating during all this. FIRST: Each film roll lasted only two minutes and forty-five seconds shooting at twenty-four frames per second, and SECOND: each wind-up was only good for a thirty-five-second shot. These factors lead to very careful seeing. You don’t press the shutter release unless you feel you’re really going to get something. In the first moments of the first day, I saw feet walking over a sign in the mud. It said, “Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses??” No one ever found out what it meant.

We ran out of time, and we ran out of film. The semester ended. Dave and Allen went back to work, and with their OK, I had the whole summer to edit, which I had never done before. Analyzing all those films with Bob Katz must have paid off, because by sitting alone, with a lot of time, doing and redoing, from assembly, to rough cut to fine cut, by the end of August, I had an edit I really liked.

One rainy night in Studio 18, a little unhappy because Allen had not shown up, I showed it silent to friends and the fall film class. They were very enthusiastic.

Then, in walked Allen, soaking wet, with a record he’d just bought under his arm, Carmina Burana. We had to show him the film, and we ran it with the record on a turntable. The film had such an amazing fit with the overwhelming chorus and spirit of Carl Orff’s music that people got up in the dark and were yelling and knocking chairs over. The breathless pace and power took the ragged people and birds and swirling junk, and lifted them immensely somewhere. Even beyond somewhere! It was mesmerizing, delicious, ridiculous, and overwhelming. So much so that without a nickel I even wrote Orff for permission to use it. Of course I never heard from him, nor did I realize that if I had gone ahead and used the music, all he could do to a broke student was say stop.

Meanwhile, I was working as a student assistant for both Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, each of whom, after seeing the film, said, “It needs some kind of musique concrète . . . something abstract.” Then Dorothea reminded me that her son-in-law, Ross Taylor, was an oboist with the San Francisco Symphony. I described the film to Ross, and he was immediately enthusiastic about doing something. Meanwhile, Dave, who hadn’t seen the film, returned from out of town, took one look at it, and said “Great, let’s get Ferlinghetti.”

The fact is, a gathering occurred on a sunny afternoon in the basement of a house on a hill above the Sunset District: Ross Taylor and three wind-instrument friends. Dave, Allen, Phil, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. We had a projector, an amateur reel-to-reel Wollensak tape recorder, one microphone on a stand, and a sheet. We put the projector outside the basement door so it could project through the door window and not be heard. We set up the recorder and the one mic. We hung the sheet, pulled up some chairs, and ran the film. It was [the] first time for Lawrence and the musicians. When it stopped there was something like a yeasty silence followed by various horns chasing various notes, and some on-and-off chitchat. After a few moments Dave said, “Shall we run it again?” They looked at each other and said, “No, let’s go for it.” So we rethreaded the projector, loaded the tape recorder and set the one level, set the mic stand up front, and rolled it. It was wild and beyond flawless . . . beyond terrific, we thought, and we all hung in mid-air as Lawrence dangled the flowerless fields of America over the dump flames. Wow. We rewound the tape, synched it with the film and ran both. It went by like some sort of amazing thing that reached out at us! It clicked, then clinched and soared, and, we thought, really worked. We sat around slightly dazed, and realized, Hey, we had it!!!! . . . in one take! No labs, no sound mixing, just magic.

We shot titles, and Monaco Lab made a print, which we sent to the Edinburgh Film Festival, which was big stuff then. It didn’t win an award, but it was accepted and shown. Later it was packaged with several short films by the USIA, the United States Information Agency, and circulated throughout the world for two years . . . Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses? being not so mute testimony to the fact that the streets of America are not paved in gold.

NZ

I think that this is where the magic began, because without a word between us, we all went in different directions and began filming. In fact, never once during the three trips we eventually made to that dump and the big one near 101 did we ever confer about what the goal was, or what we were doing. When it got near the end of class time, we simply stopped, and dropped the film off at Monaco Lab, on the way back to school. The following week we looked at the footage, thought “wow,” and went back to the dump. There was no discussion except raving over individual shots. You have to remember that there were two conscious/subconscious realities operating during all this. FIRST: Each film roll lasted only two minutes and forty-five seconds shooting at twenty-four frames per second, and SECOND: each wind-up was only good for a thirty-five-second shot. These factors lead to very careful seeing. You don’t press the shutter release unless you feel you’re really going to get something. In the first moments of the first day, I saw feet walking over a sign in the mud. It said, “Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses??” No one ever found out what it meant.

We ran out of time, and we ran out of film. The semester ended. Dave and Allen went back to work, and with their OK, I had the whole summer to edit, which I had never done before. Analyzing all those films with Bob Katz must have paid off, because by sitting alone, with a lot of time, doing and redoing, from assembly, to rough cut to fine cut, by the end of August, I had an edit I really liked.

One rainy night in Studio 18, a little unhappy because Allen had not shown up, I showed it silent to friends and the fall film class. They were very enthusiastic.

Then, in walked Allen, soaking wet, with a record he’d just bought under his arm, Carmina Burana. We had to show him the film, and we ran it with the record on a turntable. The film had such an amazing fit with the overwhelming chorus and spirit of Carl Orff’s music that people got up in the dark and were yelling and knocking chairs over. The breathless pace and power took the ragged people and birds and swirling junk, and lifted them immensely somewhere. Even beyond somewhere! It was mesmerizing, delicious, ridiculous, and overwhelming. So much so that without a nickel I even wrote Orff for permission to use it. Of course I never heard from him, nor did I realize that if I had gone ahead and used the music, all he could do to a broke student was say stop.

Meanwhile, I was working as a student assistant for both Ansel Adams and Dorothea Lange, each of whom, after seeing the film, said, “It needs some kind of musique concrète . . . something abstract.” Then Dorothea reminded me that her son-in-law, Ross Taylor, was an oboist with the San Francisco Symphony. I described the film to Ross, and he was immediately enthusiastic about doing something. Meanwhile, Dave, who hadn’t seen the film, returned from out of town, took one look at it, and said “Great, let’s get Ferlinghetti.”

The fact is, a gathering occurred on a sunny afternoon in the basement of a house on a hill above the Sunset District: Ross Taylor and three wind-instrument friends. Dave, Allen, Phil, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. We had a projector, an amateur reel-to-reel Wollensak tape recorder, one microphone on a stand, and a sheet. We put the projector outside the basement door so it could project through the door window and not be heard. We set up the recorder and the one mic. We hung the sheet, pulled up some chairs, and ran the film. It was [the] first time for Lawrence and the musicians. When it stopped there was something like a yeasty silence followed by various horns chasing various notes, and some on-and-off chitchat. After a few moments Dave said, “Shall we run it again?” They looked at each other and said, “No, let’s go for it.” So we rethreaded the projector, loaded the tape recorder and set the one level, set the mic stand up front, and rolled it. It was wild and beyond flawless . . . beyond terrific, we thought, and we all hung in mid-air as Lawrence dangled the flowerless fields of America over the dump flames. Wow. We rewound the tape, synched it with the film and ran both. It went by like some sort of amazing thing that reached out at us! It clicked, then clinched and soared, and, we thought, really worked. We sat around slightly dazed, and realized, Hey, we had it!!!! . . . in one take! No labs, no sound mixing, just magic.

We shot titles, and Monaco Lab made a print, which we sent to the Edinburgh Film Festival, which was big stuff then. It didn’t win an award, but it was accepted and shown. Later it was packaged with several short films by the USIA, the United States Information Agency, and circulated throughout the world for two years . . . Have You Sold Your Dozen Roses? being not so mute testimony to the fact that the streets of America are not paved in gold.

—written by Phil Greene on October 6, 2010, in an email to PFA curator Kathy Geritz, to be read at a screening of the film at PFA, along with Billy Woodberry’s feature film And When I Die, I Won’t Stay Dead on poet Bob Kaufman

NZ