Joan Brown’s Bathing Suits

Author

Becky Alexander

Decade

1970s 1980s 1990s

Tags

Painting Water Clothing Sports

“My sense of it is that the city and the Bay Area, for all their faults and virtues, comprise a magic ring in the world, a ring that runs in concentric circles until the final, smallest circle is centered in the water directly below the north tower of the Golden Gate Bridge, the deepest spot in the channel.”

—Gordon Cook

A redwood tree grows in the meadow of SFAI’s Chestnut Street campus, so close to the building that a student leading a follow-the-leader-style “game” in a New Genres class once jumped off the roof by the café and attempted to grab onto it, failed, fell, and broke some bones. SFAI’s resident gardener/poet/teacher Genine Lentine spends a lot of time gardening near the spot where he must have landed, and thinks often about how the things that grow there relate to the building itself. To her, that redwood is “a conduit between the meadow and the quad.” She says,

It’s interesting how the surface of even this Brutalist concrete building is embossed with wood grain. Looking up from the meadow, the redwood brings you up to the quad, where often people are standing at the edge looking down. Up on the quad, seeing the point of the treetop rising along the eastern wall feels almost like whale watching—the thrill when you catch sight of a fin. Even if you never spend time in the meadow, you might glimpse a hummingbird in the redwood’s canopy while you’re on the quad having lunch. And maybe that will make you curious to follow the tree down and explore what’s in the meadow. There’s this sparky conversation I sense between the meadow and the building, and the suggestion that there’s something further to explore is a central quality of the experience of being on this campus.My feeling is that the Bay is surely like this too, its flat expanse a parallel line against the building’s wide concrete roof. Sitting out on the roof or by the large windows of the MacMillan Conference Room or the café, you can watch the hulking container ships and cruise ships make their way slowly in and out of the Golden Gate, watch the sky as it changes with the weather and the time of day, its blues and grays reflected back by the water.

It’s possible to spend your time at SFAI more or less ignoring the Bay, but it’s also possible to get drawn in by it—perhaps literally. Swimming in those frigid waters is not for everyone, but it is very much for some. Devoted Bay swimmers congregate at the South End Rowing Club and the Dolphin Club, two rowing/swimming/handball/social clubs that sit side by side at the water’s edge, just a handful of blocks from campus. Located slightly beyond the morass of tourism that is Fisherman’s Wharf, they look like something out of a storybook. The clubs are conjoined twins—a doorway leads from one directly into the other—and both are bright white buildings, one with red trim, the other blue. The two clubs are, naturally, rivals, vying for supremacy with hotly contested annual competitions that result in a coveted plaque changing hands, or not. Outside, San Francisco is bright and busy, but inside it’s another, older, more-storied world. Dark, wood-paneled walls are covered with photographs, evidence of decades’ worth of swimming and rowing races won and lost. Beautiful old wooden boats in various states of refurbishment fill the lower levels. Upstairs, a motley assortment of San Francisco old-timers sits in the sauna, warming up from hypothermic swims (no wetsuits, if you want to retain your dignity and self-respect).

The artist Joan Brown grew up in San Francisco and enjoyed swimming in the Bay as a kid but got serious about it as an adult in the early 1970s. She had recently moved back to the city after living in the Sacramento Delta region for a few years, and was married at the time to avid Bay swimmer and fellow artist Gordon Cook. Brown’s early works were expressive, thickly painted canvases that drew influence from the Bay Area figurative movement, which had taken root at SFAI (then the California School of Fine Arts), where Brown had studied right after completing high school. But by the time she was swimming in the Bay regularly, her paintings had taken on a flatter, more graphic style and a vocabulary of imagery all her own that married the personal with the mythical. One feels Joan’s life spilling out from these canvases; they exude a sort of joy in living, a sense that the everyday stuff of life is meaningful and significant, even mystical; that it is worthy of and essential to the project of art making.

The artist Joan Brown grew up in San Francisco and enjoyed swimming in the Bay as a kid but got serious about it as an adult in the early 1970s. She had recently moved back to the city after living in the Sacramento Delta region for a few years, and was married at the time to avid Bay swimmer and fellow artist Gordon Cook. Brown’s early works were expressive, thickly painted canvases that drew influence from the Bay Area figurative movement, which had taken root at SFAI (then the California School of Fine Arts), where Brown had studied right after completing high school. But by the time she was swimming in the Bay regularly, her paintings had taken on a flatter, more graphic style and a vocabulary of imagery all her own that married the personal with the mythical. One feels Joan’s life spilling out from these canvases; they exude a sort of joy in living, a sense that the everyday stuff of life is meaningful and significant, even mystical; that it is worthy of and essential to the project of art making.

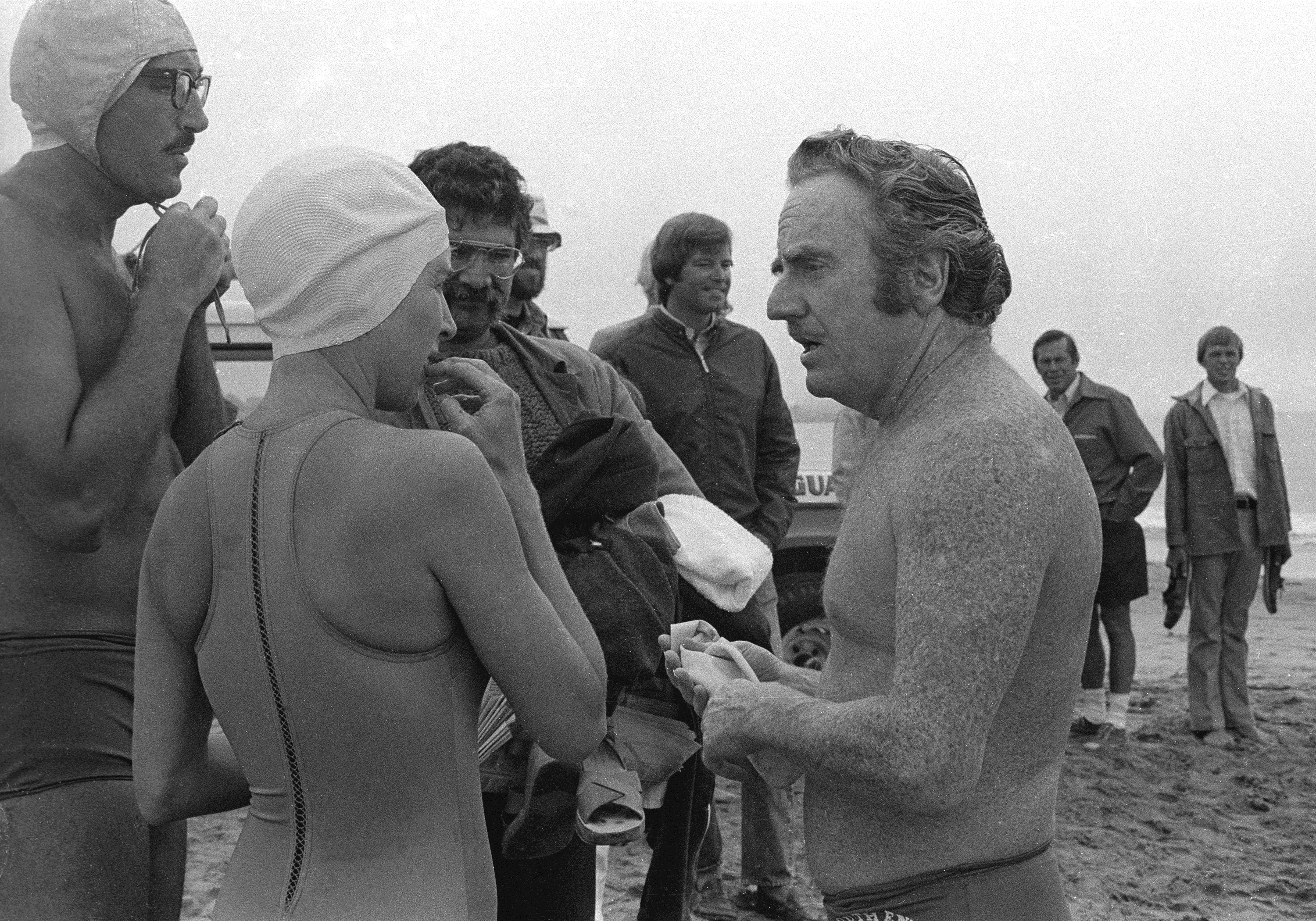

Swimming became both a subject of and fuel for Brown’s art. She painted self-portraits in and out of the water, depicting herself swimming, or thinking about swimming, or practicing swimming under the guidance of legendary San Francisco swim coach Charlie Sava. And like many Bay swimmers, she found that the practice of swimming in cold water had benefits that were not only physical but mental and spiritual. Joan explained that she would swim at the end of the day, “near sundown when the light on the water is very beautiful and peaceful. It is actually a form of meditation, and many of my ideas for paintings have materialized when I’m out on my daily swim.”

Brown became part of a community of women who shared her passion for swimming in the Bay. The South End Rowing Club, the Dolphin Club (of which her husband Gordon Cook was president at the time), and yet a third adjoining club that has since burnt down were all men-only, and women who wanted to swim were stuck changing in public restrooms or under the piers, trying not to lose their keys in the water and warming up afterward as best they could in their cars. Joan and several other frustrated women filed a class action sexual discrimination lawsuit in 1974 and won it in 1976, forcing the clubs to go co-ed.

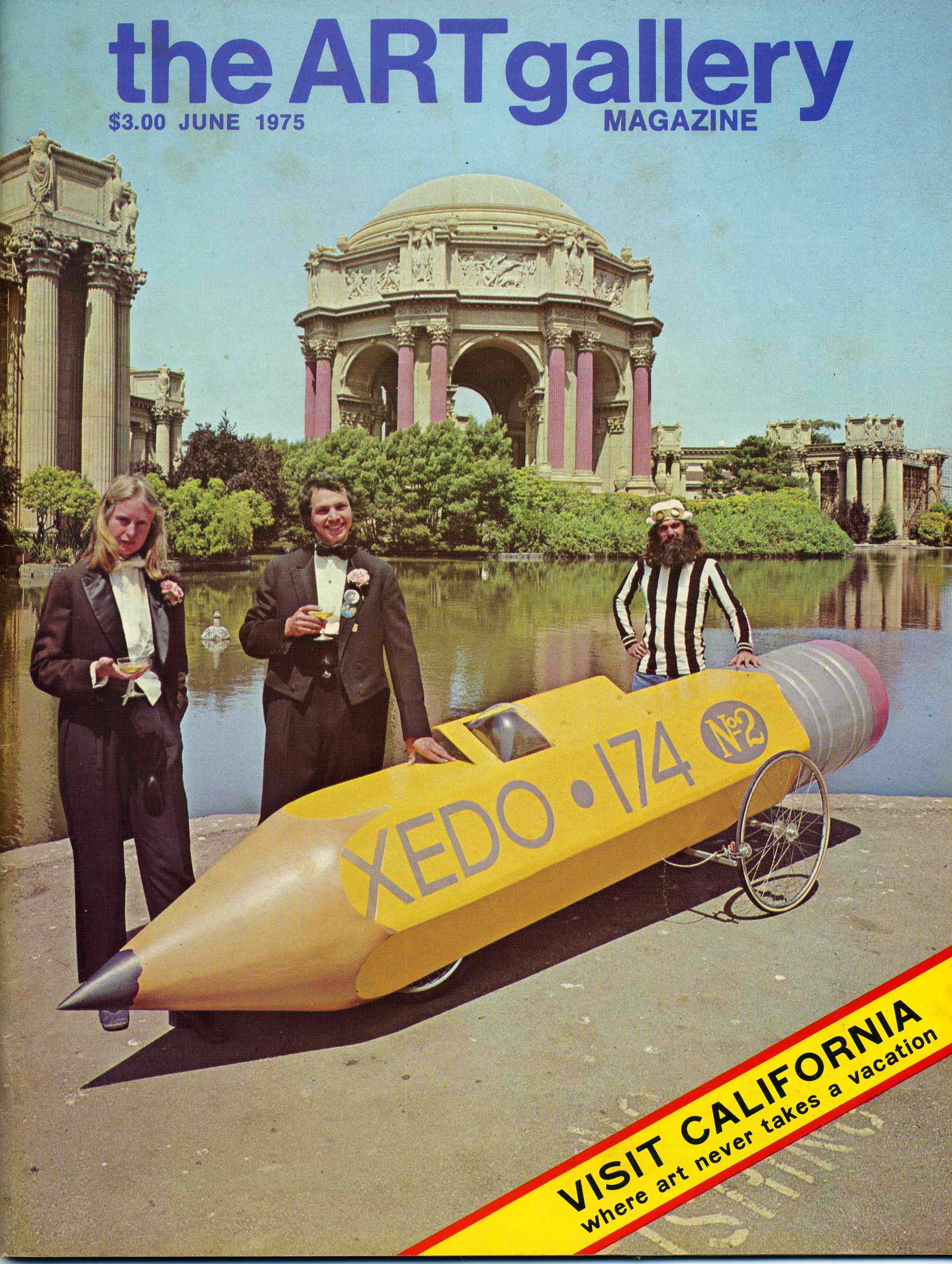

In 1975 Brown participated in a women’s Alcatraz swim, an annual tradition that involved taking a boat out to Alcatraz and swimming back across the Bay to San Francisco’s Aquatic Park. The swim went terribly for Joan and many of the other participants—they struggled with difficult currents and the wake of a passing freighter. Disoriented and in the cold water for too long, Brown became hypothermic, and had started hallucinating by the time she was pulled out of the water a quarter of a mile from the opening of the cove.

Brown became part of a community of women who shared her passion for swimming in the Bay. The South End Rowing Club, the Dolphin Club (of which her husband Gordon Cook was president at the time), and yet a third adjoining club that has since burnt down were all men-only, and women who wanted to swim were stuck changing in public restrooms or under the piers, trying not to lose their keys in the water and warming up afterward as best they could in their cars. Joan and several other frustrated women filed a class action sexual discrimination lawsuit in 1974 and won it in 1976, forcing the clubs to go co-ed.

In 1975 Brown participated in a women’s Alcatraz swim, an annual tradition that involved taking a boat out to Alcatraz and swimming back across the Bay to San Francisco’s Aquatic Park. The swim went terribly for Joan and many of the other participants—they struggled with difficult currents and the wake of a passing freighter. Disoriented and in the cold water for too long, Brown became hypothermic, and had started hallucinating by the time she was pulled out of the water a quarter of a mile from the opening of the cove.

The traumatic experience resulted in a remarkable series of paintings (you can find them here by clicking through the third row of swimming-related paintings). Each is large, around six by eight feet, and foregrounds a self-portrait: Joan sitting or standing in an interior space, her gaze contemplative, her mind elsewhere. Of her large canvases, Brown said, “I paint the size I do because I feel a participant, like I can step into the picture.” In each painting, the Bay can be seen behind her. In Before the Alcatraz Swim, she appears to be sitting by a picture window overlooking the dark profile of Alcatraz at night, but in After the Alcatraz Swim #1, #2, and #3, the Bay can be seen in paintings that are framed and hung on the wall or leaning against it. Within these paintings she depicted female swimmers, alone or as a group, struggling in or being pulled from the water.

The force of these works lies in the contrast between the stillness of the woman in each quiet interior space and the wild, dangerous chaos depicted in the painting behind her. The subject is not the fear and exhaustion of the difficult swim but the woman who holds the memory of that fear and exhaustion, who is changed and informed by her experience. How do we hold the things that have happened to us inside us, and how and why might we expose them, put a frame around them, hang them on the wall? How do our experiences mark us? In After the Alcatraz Swim #3, the figure of Joan wears a dress patterned with the repeated image of a boat—it is the freighter that came through during her swim. She wears the past on her body, but it’s just a dress, and she can choose to put it on or take it off.

The following year Joan did the swim again, this time completing it.

A word that often comes up when people talk about Joan is fearless, and a much-cited example of her fearlessness is the decision she made as a young, successful, up-and-coming artist in her twenties to change directions with her work, without regard for the pressures of the art market. Brown had been showing regularly in New York, and receiving a gallery stipend, but when her gallery saw her new paintings—spare and subdued, a real departure from the brightly expressionist impasto style of her previous work—they weren’t interested. Joan didn’t care. She cut ties and didn’t look back. It was a bold move and arguably a poor career choice, but she didn’t frame it as an act of bravery. “As far as I’m concerned,” she said, “success is an inside thing—a feeling of growth, of change, of ‘in-goingness’ in terms of the creative process—and outside means very, very little—if anything—to me, whether it is positive or negative.”2

To bow to external pressure, to meet expectations for no other reason than meeting them, was not only anathema to Joan Brown’s way of seeing herself as an artist, it was perhaps simply impossible for her. When she felt like she was repeating herself she had to stop. “I was going dead inside,” she said.3

To bow to external pressure, to meet expectations for no other reason than meeting them, was not only anathema to Joan Brown’s way of seeing herself as an artist, it was perhaps simply impossible for her. When she felt like she was repeating herself she had to stop. “I was going dead inside,” she said.3

***

One of the more colorful characters in the history of the South End Rowing Club (and I believe that the competition for this title is stiff) was a swimmer named George Farnsworth, the subject of fellow swimmer and filmmaker Judy Irving’s documentary 19 Arrests, No Convictions (2008). Farnsworth was a former strip club owner and charismatic con man who swam from Alcatraz for the seventieth time at the age of seventy-one, the oldest person to have completed the New Year’s Day Alcatraz Swim. Farnsworth was warned off cold-water swimming by his doctor after a heart attack and a triple bypass, but he ignored the advice.

George died of another heart attack in the locker room after one last swim, and I could be wrong, but I get the sense that for a lot of Bay swimmers, it doesn’t sound like such a bad way to go. Be alive, alive, alive until the day you die. Swimming in the Bay comes with a reminder that we are all humans at the mercy of the elements, at the mercy of the cold, the fog, the tides and eddies, the enormous container ships that will never spot the tiny speck of our existence so far below them in the water as they pass. Swimming in the Bay means contending with the weird flotsam and jetsam that floats around after storms—unidentifiable chunks of things, planks of wood with rusty nails poking out. Runoff after it rains ruins the water quality, but you don’t find out about it until after you’ve already swum in it; samples are collected daily, but warning signs are only posted on the beach a day after the fact. Sea lions swimming in and around Aquatic Park bump at swimmers with their noses—usually they’re just having fun, but for weeks in 2018 a sea lion went rogue and started biting people, sending a few of them to the hospital. The Bay swimmers kept swimming anyway! You can’t stop these people.

I guess you could say that Joan Brown, too, in some sense died doing what she loved, tragically and unexpectedly at the age of fifty-two, the result of an accident at a museum in India where she was installing her work. Her locker at the South End Rowing Club was just as she’d left it when she headed out of town, and her fellow swimmers had to decide what to do with its contents. This is how two of her bathing suits, bright purple and red bikinis, made their way into the archives at SFAI. SFAI librarian, archivist, and longtime South Ender Jeff Gunderson, who had a foot in each of Joan’s two worlds, added a piece of her swimming life to the historical record of her art life.

Tattoo Artist Ed Hardy studied with both Joan Brown and Gordon Cook when he was a student at SFAI. He was then focused on printmaking, and found a lot of value in the intaglio classes he took with Cook. Cook, ever-committed to drawing from life, liked to send his students out into the city with enormous etching plates on their laps to draw what they saw. According to Hardy:

![Gordon and Joan Escape the ‘90s, Don Ed Hardy, 1965-1998.]()

Hardy finished the landscape, but left the sky empty. (“I was so wiped out from doing every little house I decided it’s going to be a clear day in this print. There aren’t going to be any clouds or anything.”) He set the plate aside and focused on tattooing, only to return to it years later, in the early ’90s, when he found himself drawn back to his printmaking practice. Hardy said,

![Detail of Gordon and Joan Escape the ‘90s, Don Ed Hardy, 1965-1998.]()

Joan and Gordon were gone, and the city was changing. But the city is always changing, for better or worse, and all of us are changing with it, pushing up against the unknown and struggling toward whatever comes next, holding out, reaching out, for the feeling of being alive. Change comes with loss, but it also comes with the fun and the joy of the unexpected, something Joan Brown understood well, as a person and as an artist. Joan, in 1979:

BA

Notes

1 Horsfield, Kate, interviewer. “On Art and Artists: Joan Brown,” Profile 2, May 1982, 19.

2 Tsujimoto, Karen, and Jacquelynn Baas, The Art of Joan Brown (University of California Press, 1998), 80.

3 Brown, Joan. Lecture, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA, April 18, 1975.

4 Hardy, Don Ed and Jeff Gunderson “Don Ed Hardy and Jeff Gunderson in Conversation on Joan Brown.” San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA, November 3, 2016.

5 Horsfield, Kate, interviewer. “On Art and Artists: Joan Brown,” Profile 2, May 1982, 23.

Tattoo Artist Ed Hardy studied with both Joan Brown and Gordon Cook when he was a student at SFAI. He was then focused on printmaking, and found a lot of value in the intaglio classes he took with Cook. Cook, ever-committed to drawing from life, liked to send his students out into the city with enormous etching plates on their laps to draw what they saw. According to Hardy:

He decided that [classmate Martha Hall and I] were advanced enough and he said, ‘I want you to do an etching of the whole city of San Francisco. Go up to Twin Peaks. Sit there.’ And this plate was [huge], and over the course of, I think, a summer we would drive up there and sit there and the tour busses would come around. We’re trying to draw these things and they would go ‘oh look, artists!’ But it was great—we really busted our balls!

Hardy finished the landscape, but left the sky empty. (“I was so wiped out from doing every little house I decided it’s going to be a clear day in this print. There aren’t going to be any clouds or anything.”) He set the plate aside and focused on tattooing, only to return to it years later, in the early ’90s, when he found himself drawn back to his printmaking practice. Hardy said,

I decided to add in the sky, and what I decided to do was to create a scenario that brought it up to the present day. And what I wanted to do was to show almost a smog [of pollution from human activity] going on in the sky, the way the city had transformed from 1965 to 1998. And in this scenario up top in the upper left you can see Gordon and Joan. He’s rowing and she’s swimming. The title of the print is Gordon and Joan Escape the ’90s. At that point they’d both passed away. Gordon died in ’85 and Joan in ’90, but I thought that was kind of cool—they’re both swimming through the sky, swimming out the Gate.4

Joan and Gordon were gone, and the city was changing. But the city is always changing, for better or worse, and all of us are changing with it, pushing up against the unknown and struggling toward whatever comes next, holding out, reaching out, for the feeling of being alive. Change comes with loss, but it also comes with the fun and the joy of the unexpected, something Joan Brown understood well, as a person and as an artist. Joan, in 1979:

Success to me is still finding those surprises and the new excitement and the challenge of pushing the work just a little further each time to try to dig out that surprise that I haven’t dug out before, and that is to just keep growing and changing, to just keep letting go, and letting go of any kind of boundaries or rules or regulations that I or anybody else sets up. But what I mainly want is to be surprised, the joyousness of that surprise, going past what I know.5

BA

Notes

1 Horsfield, Kate, interviewer. “On Art and Artists: Joan Brown,” Profile 2, May 1982, 19.

2 Tsujimoto, Karen, and Jacquelynn Baas, The Art of Joan Brown (University of California Press, 1998), 80.

3 Brown, Joan. Lecture, San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA, April 18, 1975.

4 Hardy, Don Ed and Jeff Gunderson “Don Ed Hardy and Jeff Gunderson in Conversation on Joan Brown.” San Francisco Art Institute, San Francisco, CA, November 3, 2016.

5 Horsfield, Kate, interviewer. “On Art and Artists: Joan Brown,” Profile 2, May 1982, 23.