SFAI and IAIA

Author

Rye Purvis

Decade

1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s

Tags

Community Activism Painting

Racial Justice

Printmaking

An Invisible Partnership: The San Francisco Art Institute, the Institute of American Indian Arts, and the American Indian Identity in the 1960s

Since its founding in 1871, the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) has hosted many Native American and Indigenous students from all over the country. Recently, while researching Native American alumni, a connection became apparent between SFAI and the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, a large wave of students transferred from IAIA to SFAI. These students not only began an invisible partnership between Santa Fe’s illustrious IAIA and SFAI but also carved a space of belonging for Native and Indigenous students in the decades to come. To place this wave of Indigenous presence in a context of American systems converging from civil unrest, as well as a complex time for American Indian identity within the United States, we go back to the year 1965.

Since its founding in 1871, the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI) has hosted many Native American and Indigenous students from all over the country. Recently, while researching Native American alumni, a connection became apparent between SFAI and the Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe, New Mexico. Back in the 1960s and 1970s, a large wave of students transferred from IAIA to SFAI. These students not only began an invisible partnership between Santa Fe’s illustrious IAIA and SFAI but also carved a space of belonging for Native and Indigenous students in the decades to come. To place this wave of Indigenous presence in a context of American systems converging from civil unrest, as well as a complex time for American Indian identity within the United States, we go back to the year 1965.

Context of 1965

The year was 1965. It was as dynamic in its waves of political unrest as it was in forward momentum, raising awareness of injustices against Black and Brown communities in the United States. That year saw many protests in the form of teach-ins, marches, music, demonstrations, and the creation of organizations that fought for civil rights. The year prior, Indigenous folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie released her album It’s My Way!, in which a track titled “Universal Soldier” described the complexities and individual responsibilities of war, a song very much of the times, as the United States continued to increase its military presence in Vietnam. In 1965, crucial demonstrations and marches were organized in Selma by civil rights leaders demanding an end to the disenfranchisement and injustices against the Black vote and community.

The year 1965 saw a turning point for Native American identity affected by decades of tribal policies and government involvement. Many tribes and families were still feeling the effects of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, in which as many as 750,000 American Indians were moved to urban areas with promises of job security. The Relocation Act was intended to assimilate American Indians; this was one of the policies used by the US government to terminate sovereign nations and Native identity through erasure of territory, culture, and religion. In 1953, House concurrent resolution 108 “declared it to be the sense of Congress that it should be policy of the United States to abolish federal supervision over American Indian tribes as soon as possible and to subject the Indians to the same laws, privileges, and responsibilities as other US citizens. This includes an end to reservations and tribal sovereignty, integrating Native Americans into mainstream American society.”2 Like most US treaties, the Relocation Act made promises the government couldn’t keep in terms of “vocational training, housing, and financial support,”3 leaving many Native Americans in worse situations than if they had stayed on their reservations; that is, if the reservation even existed, because the US government had terminated more than one hundred tribes between 1953 and 1964.

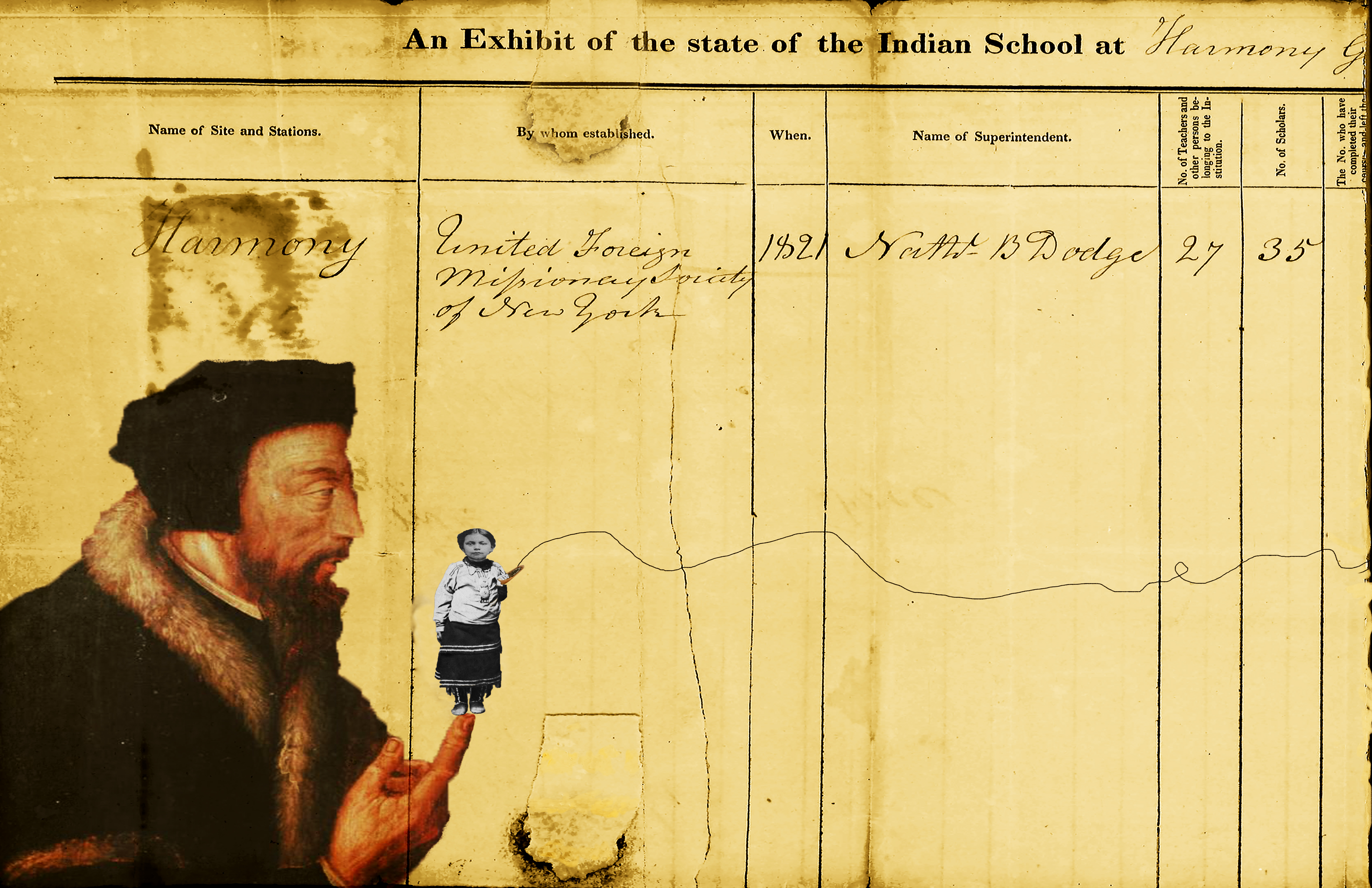

Another component of the resolve of the United States to assimilate Native Americans was the introduction of American Indian boarding schools. But the roots of these boarding schools extend back into the late nineteenth century. Largely as a response to the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, Congress encouraged “benevolent societies”4 to provide educational services in the form of boarding schools for Native Americans to be taught the “ways of the white man.”4 These educational services were primarily provided by Christian missions and the federal government. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879 by General Richard Henry Pratt (famous for his saying “Kill the Indian: Save the Man”), became a model that spurred the building of twenty-six additional boarding schools in fifteen states/territories. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had a large part in the creation of these schools, and thus in the undoing of cultural traditions.

The BIA got its start in 1824 under the US Department of the Interior, to manage the land and the health of American Indians. Concurrently the Bureau of Indian Education was brought on as a division, also under the US Department of the Interior but focused on education services. To push back against the BIA, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was founded in 1944 as an alliance among tribes who were concerned about the US government’s processes for assimilation, among many other issues. The NCAI was formed by Natives for Natives, and it initially discouraged links between those who were involved with the BIA and those who wanted to join the NCAI. The organization began as a kind of checks and balances for Native issues. The NCAI preceded the formation of several American Indian groups in the 1960s and 1970s as part of the greater Red Power movement, which demanded Native autonomy for land rights, policies, and resources. These groups were the National Indian Youth Council, American Indian Movement, Women of All Red Nations, and International Indian Treaty Council, all formed between 1961 and 1974. (The occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 by the Indians of All Tribes further heightened awareness of the oppression of Native Americans and spurred action to address it.)

The struggle for self-determination for Native Americans was gaining momentum.

Which brings us back to 1965.

Linda Lomahaftewa and the First Wave of IAIA Artists

An eighteen-year-old woman by the name of Linda Lomahaftewa entered the doors of the San Francisco Art Institute in the fall of 1965, ready to pursue a BFA after attending the newly formed Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe.

Lomahaftewa, both Hopi and Choctaw, was born in Phoenix, Arizona, and had attended IAIA as a high school student, focusing on painting in her senior year.

This was in the early days of IAIA, before it evolved into college and graduate art programs in 1975 (ultimately dropping its high school program altogether in 1979). IAIA was founded in 1962 by Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee) and Dr. George Boyce as a high school program funded by the Department of Education of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Institute stayed with the BIA until 1986, when it was “congressionally chartered as a nonprofit organization,”5 a status it holds today. Unlike other schools and institutions made for Native Americans before it, IAIA reconceptualized the model for which students were taught, promoting intertribal Native American tradition, culture and values with an innovative contemporary arts curriculum. IAIA also hired many Native American working artists as their faculty and staff.

Many artists transferred from IAIA to SFAI in the 1960s. During a conversation with current IAIA archivist Ryan Flahive, he said that the wave of students who traveled from IAIA to SFAI did so based on the recommendations of Institute faculty, and additional recommended schools were Savannah College of Art and Design, Rhode Island School of Design, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Kansas City Art Institute. For Lomahaftewa, SFAI was still close enough to home and had been recommended by advisor and instructor Jim McGrath (former director of IAIA). In a conversation with author Lawrence Abbott in 1994, Lomahaftewa said: “I applied and got accepted. It was scary but the good part about it was that a lot of us had come from Santa Fe, so we more or less went as a group together.” She continued: “I was out there during a pretty wild time, like the war protests, the peace movement, flower children. It’s a wonder I ever survived! But my whole thing was to be there to go to school, and that’s what I did.”6

The year was 1965. It was as dynamic in its waves of political unrest as it was in forward momentum, raising awareness of injustices against Black and Brown communities in the United States. That year saw many protests in the form of teach-ins, marches, music, demonstrations, and the creation of organizations that fought for civil rights. The year prior, Indigenous folk singer Buffy Sainte-Marie released her album It’s My Way!, in which a track titled “Universal Soldier” described the complexities and individual responsibilities of war, a song very much of the times, as the United States continued to increase its military presence in Vietnam. In 1965, crucial demonstrations and marches were organized in Selma by civil rights leaders demanding an end to the disenfranchisement and injustices against the Black vote and community.

The year 1965 saw a turning point for Native American identity affected by decades of tribal policies and government involvement. Many tribes and families were still feeling the effects of the Indian Relocation Act of 1956, in which as many as 750,000 American Indians were moved to urban areas with promises of job security. The Relocation Act was intended to assimilate American Indians; this was one of the policies used by the US government to terminate sovereign nations and Native identity through erasure of territory, culture, and religion. In 1953, House concurrent resolution 108 “declared it to be the sense of Congress that it should be policy of the United States to abolish federal supervision over American Indian tribes as soon as possible and to subject the Indians to the same laws, privileges, and responsibilities as other US citizens. This includes an end to reservations and tribal sovereignty, integrating Native Americans into mainstream American society.”2 Like most US treaties, the Relocation Act made promises the government couldn’t keep in terms of “vocational training, housing, and financial support,”3 leaving many Native Americans in worse situations than if they had stayed on their reservations; that is, if the reservation even existed, because the US government had terminated more than one hundred tribes between 1953 and 1964.

Another component of the resolve of the United States to assimilate Native Americans was the introduction of American Indian boarding schools. But the roots of these boarding schools extend back into the late nineteenth century. Largely as a response to the Civilization Fund Act of 1819, Congress encouraged “benevolent societies”4 to provide educational services in the form of boarding schools for Native Americans to be taught the “ways of the white man.”4 These educational services were primarily provided by Christian missions and the federal government. The Carlisle Indian Industrial School, founded in 1879 by General Richard Henry Pratt (famous for his saying “Kill the Indian: Save the Man”), became a model that spurred the building of twenty-six additional boarding schools in fifteen states/territories. The Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) had a large part in the creation of these schools, and thus in the undoing of cultural traditions.

The BIA got its start in 1824 under the US Department of the Interior, to manage the land and the health of American Indians. Concurrently the Bureau of Indian Education was brought on as a division, also under the US Department of the Interior but focused on education services. To push back against the BIA, the National Congress of American Indians (NCAI) was founded in 1944 as an alliance among tribes who were concerned about the US government’s processes for assimilation, among many other issues. The NCAI was formed by Natives for Natives, and it initially discouraged links between those who were involved with the BIA and those who wanted to join the NCAI. The organization began as a kind of checks and balances for Native issues. The NCAI preceded the formation of several American Indian groups in the 1960s and 1970s as part of the greater Red Power movement, which demanded Native autonomy for land rights, policies, and resources. These groups were the National Indian Youth Council, American Indian Movement, Women of All Red Nations, and International Indian Treaty Council, all formed between 1961 and 1974. (The occupation of Alcatraz in 1969 by the Indians of All Tribes further heightened awareness of the oppression of Native Americans and spurred action to address it.)

The struggle for self-determination for Native Americans was gaining momentum.

Which brings us back to 1965.

Linda Lomahaftewa and the First Wave of IAIA Artists

An eighteen-year-old woman by the name of Linda Lomahaftewa entered the doors of the San Francisco Art Institute in the fall of 1965, ready to pursue a BFA after attending the newly formed Institute of American Indian Arts (IAIA) in Santa Fe.

Lomahaftewa, both Hopi and Choctaw, was born in Phoenix, Arizona, and had attended IAIA as a high school student, focusing on painting in her senior year.

This was in the early days of IAIA, before it evolved into college and graduate art programs in 1975 (ultimately dropping its high school program altogether in 1979). IAIA was founded in 1962 by Lloyd Kiva New (Cherokee) and Dr. George Boyce as a high school program funded by the Department of Education of the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA). The Institute stayed with the BIA until 1986, when it was “congressionally chartered as a nonprofit organization,”5 a status it holds today. Unlike other schools and institutions made for Native Americans before it, IAIA reconceptualized the model for which students were taught, promoting intertribal Native American tradition, culture and values with an innovative contemporary arts curriculum. IAIA also hired many Native American working artists as their faculty and staff.

Many artists transferred from IAIA to SFAI in the 1960s. During a conversation with current IAIA archivist Ryan Flahive, he said that the wave of students who traveled from IAIA to SFAI did so based on the recommendations of Institute faculty, and additional recommended schools were Savannah College of Art and Design, Rhode Island School of Design, the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, and Kansas City Art Institute. For Lomahaftewa, SFAI was still close enough to home and had been recommended by advisor and instructor Jim McGrath (former director of IAIA). In a conversation with author Lawrence Abbott in 1994, Lomahaftewa said: “I applied and got accepted. It was scary but the good part about it was that a lot of us had come from Santa Fe, so we more or less went as a group together.” She continued: “I was out there during a pretty wild time, like the war protests, the peace movement, flower children. It’s a wonder I ever survived! But my whole thing was to be there to go to school, and that’s what I did.”6

During her time at SFAI, Lomahaftewa’s work transformed from abstract to landscape paintings influenced by Hopi ceremony and symbolism. In her live-model classes, she used the models as a starting point, slowly transforming the sketch into something new by incorporating her Hopi heritage. Lomahaftewa worked with faculty such as Norman Stiegelmeyer, Jack Jefferson, and Paul Harris, who taught sculpture. She was encouraged to do interdisciplinary work, which was beneficial for her when she took up printmaking in the mid- to late 1980s. Lomahaftewa received her BFA in 1970 and an MFA in 1971. Afterward, she taught at Sonoma State University and the University of California, Berkeley; she ultimately returned to IAIA, where she taught until she retired in 2017.

Lomahaftewa’s extended stay in the Bay Area was unusual for an IAIA student; for many of her IAIA peers, two months to two years was the norm for attendance at SFAI in the 1960s. Among these classmates was Washington-born Earl Biss, an enrolled member of the Crow Nation (the Apsáalooke) known for his figurative and abstract expressionist paintings. Like Lomahaftewa, Biss also worked under instructor Fritz Scholder (an enrolled member of the Luiseño) at IAIA. Scholder, a postmodern meets Pop art painter, had ties to California through previous education and exhibitions, as well as his relationships with Bay Area artists. This influence from Scholder may explain why many IAIA students in the 1960s were drawn to the Bay Area. That, and many of them had received scholarships to attend SFAI, including Biss. John Goekler describes Biss’s time at SFAI in his book Moving Paint: The Life and Art of Earl Biss (2018): “From IAIA, Earl went to the San Francisco Art Institute on a full scholarship, but found the coursework boring. . . . He also became more involved with the Red Power movement, and spent time on Alcatraz during the occupation by Native activists.”11 Regardless, Biss continued his studies at SFAI and left in 1972 to go to Europe for a year before returning to the United States. Earl Biss passed away in 1998.

Bennie Buffalo (Cheyenne), a lithographer and painter, attended SFAI from 1970 to 1972. Henry Gobin (Tulalip) attended SFAI, receiving his BFA in 1970. Doug Hyde (Nez Perce, Assiniboine, Chippewa), originally from Oregon, worked closely with sculptor and instructor Allan Houser (Chiricahua Apache), who had a great influence on Hyde during his time at IAIA. Hyde received a scholarship to attend SFAI and made the move. Although it’s unclear how long he stayed at SFAI, he enlisted in the US Army and served in Vietnam afterward. Hyde’s sculptures are in the collections of the Smithsonian Institution and the Heard Museum (Phoenix), and his Tribute to the Navajo Code Talkers is a landmark in Phoenix.

Kevin Red Star (Crow, Apsaalooka) is another notable student from IAIA, having transferred to SFAI at the same time as Lomahaftewa. Red Star is originally from Montana, and his paintings depict his Crow heritage. He received a scholarship to attend SFAI and during his stay “he was exposed to the avant garde and political and social concerns of post-modern art.”7

Other IAIA artists who transferred to SFAI between 1966 and 1970 are Earl Elder, Alfred Young Man, Karita Coffey, Roberta Tallsalt, Dominic LaDucer, Bill Prokopiof, Cliff Suathojame, Austin Rave, Alfred Clah, Ted Palmanteer, Richard Stewart, Bill Soza, Mike Romero, Arlene Schlosser, Barbara Cameron, Imogene Goodshot (Arquero), Charles Jennings, John Addison, Edison Klee, and Tui Masaniai.

T. C. Cannon and the Waves of Influence

T. C. Cannon (Kiowa, Caddo) had secured a scholarship to attend SFAI in 1966 after graduating from IAIA in 1964. Cannon was initially attracted to the Bay Area by Nathan Oliveira and Wayne Thiebaud, both of whom were figurative painters and influencers of Cannon’s IAIA instructor Fritz Scholder. Unlike Lomahaftewa, Cannon’s experience with SFAI and the Bay Area was more disillusioned. His time at SFAI ended in two months. In 1995, Bill Wallo, a close friend of Cannon, said:

“T. C. went to California in 1966 to gain further exposure to the influence of the Bay Area contemporary painters. Those painters were [working] with the successful fusion of abstract expressionist color and design and impressionist action painting. That was one kind of merger that T. C. was intrigued by. T. C. went there hoping to directly study with one or two of them who were on the faculty of the San Francisco Art Institute, but they simply never came to class! I don’t know why. The crux was that their key influences, which T. C. had been drawn to, were simply in name only and didn’t pan out in reality. There were other things in California that disorientated him, because from there, he chose to go to Vietnam.”8

Despite a two-month tenure, T. C. Cannon could arguably be one of the most prolific contemporary Native American painters to have stepped through SFAI’s doors. His work combined colorful, everyday scenes, where contemporary met tradition. A New Yorker article described his upbringing and education:

Cannon’s artwork exposes the complexities of Native American life and the ironies, relationships, and multifaceted identities that we carry. Known for his paintings, he also delved into poetry, which likewise allowed for a dialogue on the complexities of his identity as a veteran, a Native American, and a man within an American setting of the 1960s and 1970s. The promise of what could have been and where his art could go came to an end on May 8, 1978, when Cannon died in an auto accident. He was only thirty-one.

“Cannon’s father hailed from the nomadic Kiowa, of the Southern Plains, and his mother from the Caddo, who were forcibly displaced from the Southeast to the Indian territories of Oklahoma. (His father was also half Scotch-Irish.) Cannon chose to enroll as Kiowa, with a name, Pai-doung-u-day, that translates as ‘one who stands in the sun.’ Having grown up in a mostly white small town, Gracemont, he had the good fortune, in 1964, to enter the Institute of American Indian Arts, an energetic school that had recently been founded, in Santa Fe, by the federal Bureau of Indian Affairs. There, he saw a lot of work by the Kiowa Six, a cohort of early-twentieth-century artists whose crisp paintings of tribal dancers and ceremonial figures, in boldly outlined flat colors, were prized by collectors. But Cannon seemed to dismiss derivations of that mode as ‘cartoon paintings of my people that grace mansions at a going rate of nothing.’ He developed, instead, his idiosyncratic synthesis of cosmopolitan styles.”9

Cannon’s artwork exposes the complexities of Native American life and the ironies, relationships, and multifaceted identities that we carry. Known for his paintings, he also delved into poetry, which likewise allowed for a dialogue on the complexities of his identity as a veteran, a Native American, and a man within an American setting of the 1960s and 1970s. The promise of what could have been and where his art could go came to an end on May 8, 1978, when Cannon died in an auto accident. He was only thirty-one.

Cannon’s influence continued after his death. The San Francisco Art Institute started the T. C. Cannon Scholarship in his honor, for Native American students in the 1990s. Doug Smarch Jr. (Tlingit) was the first recipient of this award, after graduating from IAIA with an associate’s degree in 1999. Smarch gained his BFA from SFAI in 2001 and his MFA from UCLA in 2004. His artwork consists of mixed media, sculpture, and CG animation. I also received the T. C. Cannon Scholarship, without which college in the Bay Area would not have been accessible. I am grateful to Cannon for artistic inspiration, as well as personally.

A Twenty-First-Century Outlook

The 1960s and 1970s Native American artists from IAIA, including Linda Lomahaftewa, T. C. Cannon, and Kevin Red Star, paved the way for artists like Doug Smarch Jr. to define presence and Native vision within SFAI’s history and legacy. In the 1980s and 1990s, Zig Jackson (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) entered SFAI, gaining his MFA in photography in 1994, and he taught photography at IAIA with nationally known photographer Meridel Rubenstein. Jackson’s body of work explores Native identity through self-portraits, playing with the context of the subject matter interacting with the notion of property, land rights, stereotypes, touristry, and self-reflection. “Dealing with a culture in transition and its fight to survive within the confines of a foreign social structure and economic framework,” Jackson says in his artist statement, “my imagery explores the inherent ironies engendered by the confrontation of two opposing cultures and belief systems—including contemporary issues of identity and representation, displacement, land rights, indigenous sovereignty, and the ambiguity of cultural boundaries.”10

Acknowledging a sense of displacement and representation is a common thread for many artists I spoke to for this project. Of moving to the Bay Area in 1965, Lomahaftewa said, “It was scary at first. I did miss home a lot; there were a lot of times I wanted to quit, I wanted to be back home, but my family was encouraging me to push to finish.” Lomahaftewa also mentioned that there wasn’t a lot of diversity at SFAI during that time, yet she and her Native peers became a type of support group for each other. The need for community and recognition of American Indian identity in higher education still resonates decades later, in my talks with Native American students who attended SFAI more recently. This piece about going “back home” for various reasons came up in a few conversations with recent SFAI alumni Jen Tiger and Nizhoni Ellenwood.

Jen Tiger (Osage) attended SFAI in 2015–16, deciding to pursue her interest in photography. Instead of making the move from IAIA to SFAI, her journey has been the opposite. On the suggestion of her sister, she transferred to IAIA in 2018. While at SFAI, she had worked with professors Elizabeth Bernstein and Linda Connor, developing not only the formal training of her photographic practice but the conceptual side as well. Tiger began to explore the missionization of California’s tribes not as a photographic project but as a beginning point of research. This exploration prompted her to look into her own tribe’s history, and she took a leave of absence from SFAI and returned to Osage reservation. For Tiger, the move back was research-based, because the source of information was there. She combed through historical societies’ online collections, libraries, and missionary journals, and visited sites in Kansas and Missouri, where some of the missions were located. Since then she has created a beginning series of mixed-media pieces from her mission project and continues her research. She is also exploring metal and how Osages adapted trade silver into their regalia.

A Twenty-First-Century Outlook

The 1960s and 1970s Native American artists from IAIA, including Linda Lomahaftewa, T. C. Cannon, and Kevin Red Star, paved the way for artists like Doug Smarch Jr. to define presence and Native vision within SFAI’s history and legacy. In the 1980s and 1990s, Zig Jackson (Mandan, Hidatsa, Arikara) entered SFAI, gaining his MFA in photography in 1994, and he taught photography at IAIA with nationally known photographer Meridel Rubenstein. Jackson’s body of work explores Native identity through self-portraits, playing with the context of the subject matter interacting with the notion of property, land rights, stereotypes, touristry, and self-reflection. “Dealing with a culture in transition and its fight to survive within the confines of a foreign social structure and economic framework,” Jackson says in his artist statement, “my imagery explores the inherent ironies engendered by the confrontation of two opposing cultures and belief systems—including contemporary issues of identity and representation, displacement, land rights, indigenous sovereignty, and the ambiguity of cultural boundaries.”10

Acknowledging a sense of displacement and representation is a common thread for many artists I spoke to for this project. Of moving to the Bay Area in 1965, Lomahaftewa said, “It was scary at first. I did miss home a lot; there were a lot of times I wanted to quit, I wanted to be back home, but my family was encouraging me to push to finish.” Lomahaftewa also mentioned that there wasn’t a lot of diversity at SFAI during that time, yet she and her Native peers became a type of support group for each other. The need for community and recognition of American Indian identity in higher education still resonates decades later, in my talks with Native American students who attended SFAI more recently. This piece about going “back home” for various reasons came up in a few conversations with recent SFAI alumni Jen Tiger and Nizhoni Ellenwood.

Jen Tiger (Osage) attended SFAI in 2015–16, deciding to pursue her interest in photography. Instead of making the move from IAIA to SFAI, her journey has been the opposite. On the suggestion of her sister, she transferred to IAIA in 2018. While at SFAI, she had worked with professors Elizabeth Bernstein and Linda Connor, developing not only the formal training of her photographic practice but the conceptual side as well. Tiger began to explore the missionization of California’s tribes not as a photographic project but as a beginning point of research. This exploration prompted her to look into her own tribe’s history, and she took a leave of absence from SFAI and returned to Osage reservation. For Tiger, the move back was research-based, because the source of information was there. She combed through historical societies’ online collections, libraries, and missionary journals, and visited sites in Kansas and Missouri, where some of the missions were located. Since then she has created a beginning series of mixed-media pieces from her mission project and continues her research. She is also exploring metal and how Osages adapted trade silver into their regalia.

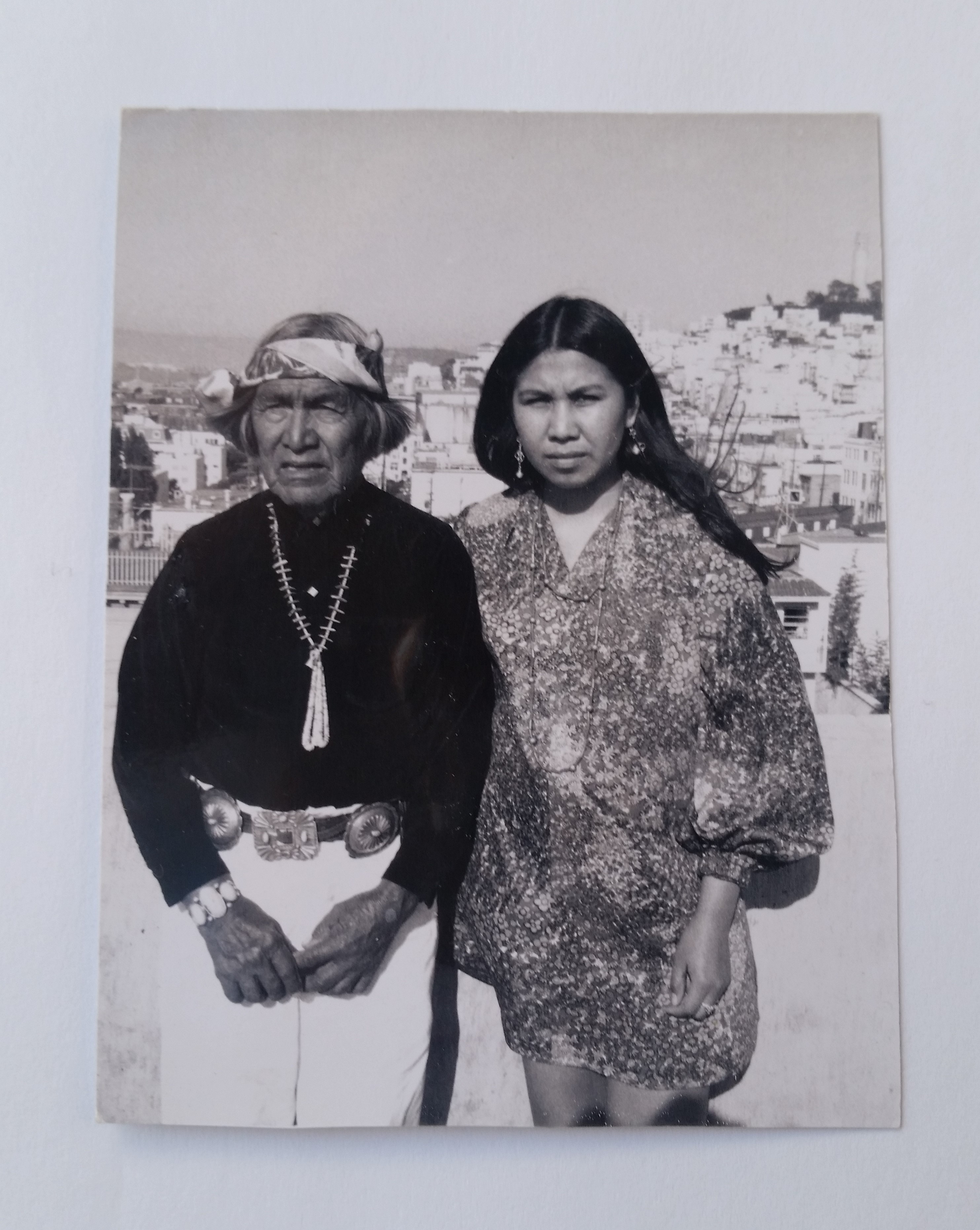

An alumna with no IAIA connection, Nizhoni Ellenwood (Nii Mii Puu/Nez Perce and Apache) attended SFAI from 2005 to 2010, gaining her BFA in photography. Unlike the artists mentioned above, Ellenwood was born and raised in the Bay Area. Her family, in particular her dad’s side, were originally from Idaho but, due to the Relocation Act, found themselves in the Bay Area. Ellenwood left the Bay Area in 2013 to lend support with the burying of her father but ended up staying longer in Idaho, to live and reconnect with family. She recalled visiting her grandfather, and listening to him speak Nez Perce: “I was able to sit with him and hear his stories. I would have never had the chance to do that if I hadn’t gone back. I also learned how to weave traditionally from our elders and hear them speak in our language. The connection is so intense, between going back home and all that influences me, I think about that daily, whether it’s speaking in my language, or in my artwork.” The move back to Idaho influenced her artwork through weaving, textiles, regalia making, and basketry, along with furthering her photography. Since then, Ellenwood has continued her weaving and textile work, and has returned to California with her son.

Having grown up in the Bay Area, Ellenwood saw firsthand what the Native representation is capable of through events such as Bay Area community Powwows put together by San Francisco State University’s Student Kouncil of Intertribal Nations (SKINS) group. Attending SFAI in 2005 brought hope to Ellenwood that similar Native representation would be emulated in SFAI’s halls. This wasn’t the case. Driven by the lack of representation both inside and outside the classroom, Ellenwood created a student group with the help of fellow student Richard Castaneda, an SFAI MFA photographer and IAIA alumnus. The Indigenous Arts Coalition (IAC) bridged a gap of representation that she, Castaneda, and other Native and Indigenous students were missing: a place for critique, conversation, exhibition, and belonging. I, too, yearned for that sense of belonging in 2007 and since then have met and collaborated with Ellenwood, Castaneda, Spencer Keeton Cunningham, Erick Andino, Avanna Lawson, Erlin Geffrard, Daniel Rodriguez, Arianna Fields, and other alumni who connected with the group.

The Bay Area is home to the Ohlone, Chochenyo, Ramaytush, Karkin, Yokuts, Graton Rancheria (Coast Miwok and Southern Pomo), Kashaya, Patwin, Mishewal Wappo, Bay Miwok, and Muwekma,12 and the region has had a prominent role in fostering contemporary Indigenous artists and artwork. Outside SFAI, the rich history and examples of resilience are numerous. American Indian Contemporary Arts, founded by Janeen Antoine (Rosebud Sioux) in 1982, continues to serve as a well of knowledge and a space for Indigenous vision. The Native American Health Center, the American Indian Film Institute, and the Intertribal Friendship House have provided workshops, exhibitions, and acknowledgment for contemporary Native American artists. The future looks promising: the American Indian Cultural Center of San Francisco has relaunched (from its start in 1968), seeking to reestablish a physical presence in the Bay Area that could serve as a space for artists as well. The Bay Area has one of the largest populations of Intertribal Native Americans in the United States, and it holds a crucial space for Intertribal history and reflection.

The connection with IAIA perhaps influenced many of the Native American and Indigenous artists in their journeys beyond SFAI, through their artistic practices, exhibitions, and connections to each other. Acknowledgment of this thread between institutions is a step in acknowledging the prevailing work and vision that came out of the waves of artists connected to a shared experience in the Bay Area. I hope to continue this personal research, acknowledging more of these artists who influence Native American art today, as well as recognizing the importance of having a place and sense of belonging for Native vision in higher education, the fine arts, and the Bay Area. This is only the beginning.

Thank you to Linda Lomahaftewa, Tatiana Lomahaftewa-Singer, Ryan Flahive, Stephanie Stewart, Jen Tiger, and Nizhoni Ellenwood; to the knowledgeable SFAI library team, including Becky Alexander, Nina Zurier, and Jeff Gunderson; and to the Heard Museum for your time and support.

This essay is dedicated to my mother, Aurelia, whose birthday would have been today, August 18. She taught me strength, resilience, humor, and hard work. She supported me in my pursuit of education in the Bay Area. I will miss you forever, Hágooshį́; this one’s for you.

The connection with IAIA perhaps influenced many of the Native American and Indigenous artists in their journeys beyond SFAI, through their artistic practices, exhibitions, and connections to each other. Acknowledgment of this thread between institutions is a step in acknowledging the prevailing work and vision that came out of the waves of artists connected to a shared experience in the Bay Area. I hope to continue this personal research, acknowledging more of these artists who influence Native American art today, as well as recognizing the importance of having a place and sense of belonging for Native vision in higher education, the fine arts, and the Bay Area. This is only the beginning.

Thank you to Linda Lomahaftewa, Tatiana Lomahaftewa-Singer, Ryan Flahive, Stephanie Stewart, Jen Tiger, and Nizhoni Ellenwood; to the knowledgeable SFAI library team, including Becky Alexander, Nina Zurier, and Jeff Gunderson; and to the Heard Museum for your time and support.

This essay is dedicated to my mother, Aurelia, whose birthday would have been today, August 18. She taught me strength, resilience, humor, and hard work. She supported me in my pursuit of education in the Bay Area. I will miss you forever, Hágooshį́; this one’s for you.

RP

Notes

1 Wikipedia, s.v. “Selma to Montgomery marches.”

2 Wikipedia, s.v. “House concurrent resolution 108.”

3 Wikipedia, s.v. “Red Power movement.”

4 Wikipedia, s.v. “Civilization Fund Act.”

5 Wikipedia, s.v. “Institute of American Indian Arts.”

6 Lawrence Abbott, ed., I Stand in the Center of the Good (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1994), 149–59.

7 Wikipedia, s.v. “Kevin Red Star.”

8 Joan Frederick, T. C. Cannon: He Stood in the Sun (Flagstaff, AZ: Northland, 1995), 37.

9 Peter Schjeldahl, “T. C. Cannon’s Blazing Promise,” New Yorker (April 8, 2019).

10 Zig Jackson, artist statement.

11 John Goekler, Moving Paint: The Life and Art of Earl Biss (American Design, 2018).

12 Indigenous Populations in the Bay Area.