Ghost

Author

Becky Alexander

Decade

1920s 1930s 1940s 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s 2010s

Tags

Clothing Ghost

Performance

Relics The Tower

The Unknown

A uniquely strong and early advocate for the presence of a ghost in SFAI’s tower was a painter named Bill Morehouse, a student in the late 1940s who made some cash on the side doing odd jobs for the school and serving as its night watchman. Articles about SFAI’s ghost have shown up in various local publications over the years, and Morehouse features prominently in pretty much all of them, at one point even arranging for a San Francisco Chronicle reporter to spend a night alone in the tower in order to experience the ghost for himself!1 (He did not.) Apparently Morehouse actually lived in the tower off and on during this time, initially while working on outfitting one of its rooms as living quarters for the school’s janitor2, and purports to have encountered the ghost on his very first night sleeping up there. This is how he explained it to the Chronicle, years later:

It was around midnight, and I had just gone to bed on the third level. I heard the doors opening and closing down below, and, presuming it was my friend, the janitor, I didn’t bother to investigate. Then I heard the steps coming up to my floor. The door to my room opened and closed as if someone had entered. It was a large chamber, well illuminated, and in it was just a water tank, my bedroll, and myself. There was no one there. The footsteps went through the room and back to the door. The knob turned, the door opened and closed again, and the footsteps continued up to the observation platform.3

Morehouse managed to stick it out, but “nailed his door shut for the remainder of the night.” (Debatable how much of a deterrent that would be for a ghost?)

Additional reports of paranormal activity came from other students and staff around this time, particularly those who had reason to be in the building at night. Faculty member Wally Hedrick was working late when he heard “all the tools go on downstairs in the sculpture studio. Hurrying down to investigate, he found no one.” Hayward King was SFAI’s Evening Registrar, a job which included walking around and turning off all the lights before closing the building at the end of the day. According to Hayward, “Just before going out we’d turn and look back. Often we’d find that one or two lights were on again in the empty building. Of course, you could say that we’d missed those lights or there was a short in the electricity. You could say a lot of things . . .”4

The tower continued to be used as a weird, chilly apartment in the early 1960s, perhaps one reason why this seems to have been such a well-haunted era. Student Bob Hudson had taken on the night watchman gig in 1962, and recalled sitting outside, eating a sandwich, “when I looked up [at the tower] and saw a woman standing in the arches at the top wearing a baby blue dress.” Hudson hurried to the tower and raced up the stairs, but no one was there.5

One question that emerges from all of these ghost stories: What kind of a ghost are we talking about here? Does the ghost have a gender, a temperament, a method to or motivation for its haunting? Bill Morehouse and his friends concluded for whatever reason that the spirit was male and “mischievous but fundamentally benign,” but in the late ’60s, as construction was underway for the building expansion, the stories took a darker turn. Perhaps the ghost was annoyed by all the noise and disruption, or cramped by the tower’s conversion into storage for the Art Bank, a collection of works by artists in the SFAI community that were included in touring shows from the late ’50s through the ’60s. One way or another it was blamed not only for various personal misfortunes (“a bad motorcycle accident, an attack of polio, a serious family problem”6), but for the delayed opening of the new building itself.

And another question: If a building lasts long enough, do its ghosts come and go, or do they just keep piling up, generation upon generation of banging, rattling, stair-climbing, door-opening, light-switch-switching restless souls? Maybe the tower’s haunting has been a group effort? In 1976 SFAI threw a Halloween party “in honor of the ghost who haunts the seventy-five-year-old tower of the Art Institute.” Per the announcement:

And another question: If a building lasts long enough, do its ghosts come and go, or do they just keep piling up, generation upon generation of banging, rattling, stair-climbing, door-opening, light-switch-switching restless souls? Maybe the tower’s haunting has been a group effort? In 1976 SFAI threw a Halloween party “in honor of the ghost who haunts the seventy-five-year-old tower of the Art Institute.” Per the announcement:

An evening of the occult is planned with palmists, physiognomists, astrologists, tarrot [sic] and tea leaf readers, numerologists and graphologists. [. . .] Dancing, followed by a midnight supper will be held. The supper will consist of Hor d’oeuvres Medusa, Eye of Newt Tidbits, Wing of Bat, Leg of Lizard, Portugese [sic] Skeleton Soup, Blood Spread on Bone Bread, Dinosaur Bones, Frog Legs in Formaldehyde (available in season)

In preparation for the event, three mediums—Amy Chandler, Sylvia Brown, and Macelle Brown—were brought in to perform a seance in the tower. Also in attendance? Bill Morehouse, of course, now almost thirty years out from his original spectral encounter. Amy declared the place full of all sorts of ghosts—“actually more spirits than people.” But Sylvia focused in on one in particular. According to the official press release for the event

Those present sat in a circle in the Tower. Candles and water were present as possible signs of phenomenological evidence. Trans-medium Sylvia Brown entered a deep trance, receiving information from a spirit guide called Francine. Francine spoke through Sylvia’s body and revealed that the Tower spirit manifested to Bill Morehouse in the 1950s was a previous incarnation—someone who Bill himself had been in a previous life. This non-malevolent spirit was associated with New England, with the sea, and with whaling. Bill acknowledged that he feels very close to these things.7

In the years after the Art Bank was disbanded, other types of storage gradually took over the space—the library’s 16mm film collection, old institutional records. Eventually a phone line was run up to the bottom room and the school’s designer had his office in there for a while. At some point along the way a window in the top room was inadvertently left open and some pigeons managed to get inside. By the time this was discovered, they had made themselves at home. The pigeons were shooed out but the room was declared a biohazard, locked, and left alone for the next decade or so.

I had started working at SFAI by the time the top room of the tower was finally opened up again and cleared out. The library staff went in before it all got trashed to see if there were any documents worth salvaging. I wish I had taken pictures of how the room looked then. At some point a loft had been installed for added storage, and both levels were full of boxes and stacks of paper that had been sitting there for years, untouched by people (and really, as far as I could see, not very touched by pigeons either), but gently dripped upon by the water that leaked in through the ceiling whenever it rained. The leaks had slowly saturated the boxes and the boxes had slowly fallen apart, releasing cascades of paper that gently fanned out as they fell and then stayed that way, in perfect, otherworldly formations. That top room stayed empty for a long time after the big cleanout, and in 2015 instructor Thor Anderson took advantage of its emptiness by turning it into a giant camera obscura, covering the windows completely except for a single quarter-inch opening. As your eyes adjusted to the darkness, a view of the outside world came into focus on the walls—silent, upside down, a phantom city with tiny blurs of people and cars passing through.

I had started working at SFAI by the time the top room of the tower was finally opened up again and cleared out. The library staff went in before it all got trashed to see if there were any documents worth salvaging. I wish I had taken pictures of how the room looked then. At some point a loft had been installed for added storage, and both levels were full of boxes and stacks of paper that had been sitting there for years, untouched by people (and really, as far as I could see, not very touched by pigeons either), but gently dripped upon by the water that leaked in through the ceiling whenever it rained. The leaks had slowly saturated the boxes and the boxes had slowly fallen apart, releasing cascades of paper that gently fanned out as they fell and then stayed that way, in perfect, otherworldly formations. That top room stayed empty for a long time after the big cleanout, and in 2015 instructor Thor Anderson took advantage of its emptiness by turning it into a giant camera obscura, covering the windows completely except for a single quarter-inch opening. As your eyes adjusted to the darkness, a view of the outside world came into focus on the walls—silent, upside down, a phantom city with tiny blurs of people and cars passing through.

SFAI’s ghost has made it onto various “Haunted San Francisco” lists, so of course ghost hunters show up from time to time. Some came by in 2008 that I don’t particularly remember, and others came in 2012 that I do—they set up shop in the tower’s top room for a few hours, bringing along their ghost-detection equipment and a bottle of vodka that they opened up in order to attract the perhaps-Russian ghosts of Russian Hill. They went so far as to play Russian folk music for these theoretical Russian ghosts (although they also played some Queen—covering the bases). I have heard the rumor—but so far have seen no evidence—that the land the school sits on was once a graveyard. And apparently a Gold Rush–era Russian graveyard did give Russian Hill its name, but the general consensus is that it was likely six blocks away, north of Vallejo between Taylor and Jones. There’s a plaque over there now—a gift of the Russian government(!)—stating this, at any rate. I’m not sure why that particular handful of Russian ghosts would have felt the need to trek over to SFAI to do their haunting.

![Letter to archivist Harry Mulford from SFAI President Stephen Goldstine.]()

But even if the death and sorrow that you suspect might be lurking in a place turns out to be lurking a fifteen-minute walk away, maybe it doesn’t matter—the world has plenty of sorrow to go around, and every building has seen its share. In 1985, some SFAI faculty members told the Bay Guardian that they’d encountered what they thought was “the spirit of a young woman who allegedly committed suicide on the tower steps long ago.”8 I’ve heard variations of this myself, including the rumor that someone once jumped from the platform at the top of the tower. Not true, but you can see how those stories might have taken root considering other things that are true: that a former SFAI president once committed suicide, that years ago a student hanged himself in Studio 8.9 There’s something fundamentally strange about the way a thing like that can occur in a place and leave no trace. Though I don’t believe in ghosts myself, I do appreciate the work they do, the message they send forward from the past: something happened here.

Lately the archival storage that had previously taken over the bottom two rooms of the tower has crept up into the top room as well, so now at a bare minimum the tower is full of the kinds of ghostly presences that lurk in the pages of old letters and documents, giving us what all ghosts have to offer: glimpses of long-gone people and perhaps-unanswerable questions, their mere presence an assertion that the past is never really gone, that it is always waiting to be reckoned with. The archives contain a “Ghost File” of course (the source of most of what you’ve just read). One particularly striking document that made its way into the file is a description of the plan for a performance piece that then-student Richard Irwin (or “Irwin-Irwin,” his stage name) intended to carry out on October 27, 1978. (MIDNIGHT was written and then scratched out as the starting time, replaced by the more reasonable 8:00 PM.) Assuming all went as planned, Irwin dressed in black, put a cloth over his head, and, witnessed by an audience watching a live video feed in Studio 10, crawled slowly up the tower steps until he reached the top, where a Ouija board was waiting, along with a thin sheet of 8 1/2-by-11-inch glass hanging from the ceiling:

And then:

But even if the death and sorrow that you suspect might be lurking in a place turns out to be lurking a fifteen-minute walk away, maybe it doesn’t matter—the world has plenty of sorrow to go around, and every building has seen its share. In 1985, some SFAI faculty members told the Bay Guardian that they’d encountered what they thought was “the spirit of a young woman who allegedly committed suicide on the tower steps long ago.”8 I’ve heard variations of this myself, including the rumor that someone once jumped from the platform at the top of the tower. Not true, but you can see how those stories might have taken root considering other things that are true: that a former SFAI president once committed suicide, that years ago a student hanged himself in Studio 8.9 There’s something fundamentally strange about the way a thing like that can occur in a place and leave no trace. Though I don’t believe in ghosts myself, I do appreciate the work they do, the message they send forward from the past: something happened here.

Lately the archival storage that had previously taken over the bottom two rooms of the tower has crept up into the top room as well, so now at a bare minimum the tower is full of the kinds of ghostly presences that lurk in the pages of old letters and documents, giving us what all ghosts have to offer: glimpses of long-gone people and perhaps-unanswerable questions, their mere presence an assertion that the past is never really gone, that it is always waiting to be reckoned with. The archives contain a “Ghost File” of course (the source of most of what you’ve just read). One particularly striking document that made its way into the file is a description of the plan for a performance piece that then-student Richard Irwin (or “Irwin-Irwin,” his stage name) intended to carry out on October 27, 1978. (MIDNIGHT was written and then scratched out as the starting time, replaced by the more reasonable 8:00 PM.) Assuming all went as planned, Irwin dressed in black, put a cloth over his head, and, witnessed by an audience watching a live video feed in Studio 10, crawled slowly up the tower steps until he reached the top, where a Ouija board was waiting, along with a thin sheet of 8 1/2-by-11-inch glass hanging from the ceiling:

Sitting on the floor, placing my hands on the Ouija board, I ask “is there a spirit present.” If the answer is “no” or “yes” I respond accordingly. If I receive no contact I end the piece by breaking the sheet of glass against my forehead. If contact is established, upon satisfaction that this activity is completed the act of breaking the glass nevertheless transpires.

And then:

Performance ends after I have broken the glass and proclaim:

“WE ARE IN THE TOWER

THE TOWER IS IN US”

Was contact established? I looked through the rest of the Ghost File as well as the file devoted specifically to Richard Irwin, but the archives are silent on this point. And maybe someone who was there that night remembers, and maybe no one does. Sadly, Richard himself can’t tell us—he died of AIDS in 1989. Wondering about him, poking around online, I found something written last August [2018] by a woman named Rebecca LaFontaine-Larivee. Rebecca met and dated Richard when he was thirty-six, only a handful of years before he died. He was still living in San Francisco then, working as a groundskeeper at the Palace of Fine Arts back when it was home to the Exploratorium, listening to the foghorns at night, watching films at the Roxie, still performing, performing even after he got sick. Rebecca held on to Richard’s coat after he died. She held on to it for thirty years. And then she gave it away:

The essay is easy to find online,10 at least for now, but I printed it out and stuck it in his file anyway, for you, or someone else, to come across later.

BA

Notes

1 Dean Wallace, “A Lively Ghost Problem: The Haunted Art Tower,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 25, 1963.

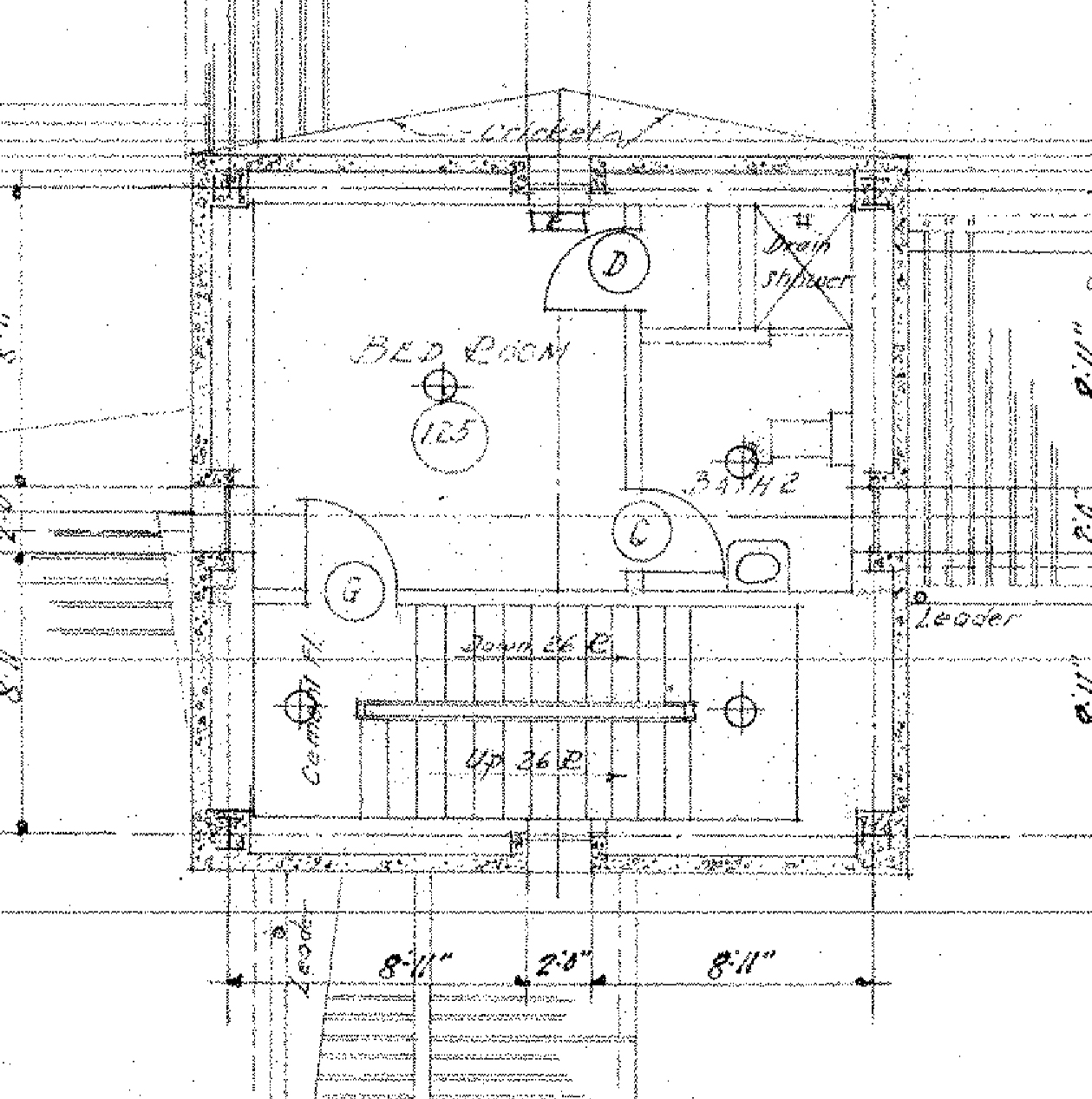

2 I haven’t yet figured out what, if anything, the tower was used for before that. The blueprints show a water tank in the top room, an empty middle room, and a bottom room labeled BEDROOM, with a closet and tiny bathroom in one corner. Early correspondence confirms that this was more or less the original plan—a 1927 letter from then-president Walter S. Martin to the architects of the brand-new building asks why the heating system doesn’t extend up into the tower rooms, which were “intended to be used either as Rest Rooms for the faculty, or as quarters for the janitors or porters.” Maybe unsurprisingly, the answer was budget-related. The architects responded that “[t]he building was constructed under the Cost-plus plan and economy was apparently the watch word at the time. In the interest of economy this heating was left out entirely.” They then suggest an electric space heater (“The Majestic type is probably the best of the lot.”). For this or whatever reason, it seems that the tower wasn’t actually converted into living quarters until Morehouse worked on the project in the ’40s. Today you can still see evidence of the tower’s former life as a residence, with pipes that once were used for plumbing poking up through the floor and a mirrored cabinet mounted on a wall where a sink would have been.

3 Gail Sullivan, “How About a Ghost Story?,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle, January 9, 1972.

4 Ibid.

5 “Art Institute Puts Ghost to Work,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 1976.

6 “A Ghost of Legend Haunts the Artists,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1968.

7 Bill Morehouse died in 1993. I have no idea what sort of unfinished business he may or may not have had in this life, but if given the option, I can think of one spot Bill might have chosen to haunt in a “mischievous but fundamentally benign” sort of way.

8 Myriam Weisang, “Hearts for Art’s Sake: A Profile of the San Francisco Art Institute and Its Second Annual Artists’ Valentines Exhibition/Auction,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, February 6, 1985.

9 This strange and terrible story crops up in Reflections from a Cinematic Cesspool, a very funny and wild sort of book written by the filmmaker George Kuchar, who taught at SFAI for forty years, up until 2011, the year of his death. George always taught in Studio 8, and the films his classes put together over the course of the semester were invariably awash in wigs and disguises and weird makeup and jury-rigged sets. George came into the studio to set up for class and saw what he took to be a dummy dressed up in clothes from the prop closet hanging from the lighting grid. He was so used to that kind of thing that it took him a while to realize that it wasn’t.

10 Rebecca LaFontaine-Larivee, “Richard’s Coat: Remembering Richard Irwin,” Empty Mirror, https://www.emptymirrorbooks.com/personal-essay/richards-coat(accessed April 10, 2019).

As I drove home, my chest tightened and I began to cry. A grief overcame me that had been absent since that distant time in 1989 when Richard folded his arms over his chest—silently asking permission to die. My hands shook on the steering wheel as I drove back to Corrales and I considered going back to the store to retrieve the coat. I practiced the speech I would make to the store manager: “Sorry ma’am, I’ve made a mistake leaving that. I promise I will pay you for the inconvenience.” Instead, I came home to my apartment, burned a log on the fire, and made myself some tea. I also watched the sun go down on the Sandia Mountains, giving them the “watermelon” hue that they are named for. Friends lost and times past darted through my mind as I mourned the rich exuberance of youth. Then as the moment passed and calmness settled in, I began to question how a scrap of cloth could bring back a life or how its absence could erase a memory. I pictured Richard as I will always see him from a photograph I had taken in Golden Gate Park. He was standing in front of the entrance of a pedestrian tunnel with shadows behind him and cement stalactites hanging down. Wearing a black leather jacket zipped up against the cold, he was trying to look serious as he was gazing at me, but his boyish smirk gave him away. The image had become increasingly faded over the years but I felt this time he’d come to say goodbye.

The essay is easy to find online,10 at least for now, but I printed it out and stuck it in his file anyway, for you, or someone else, to come across later.

BA

Notes

1 Dean Wallace, “A Lively Ghost Problem: The Haunted Art Tower,” San Francisco Chronicle, June 25, 1963.

2 I haven’t yet figured out what, if anything, the tower was used for before that. The blueprints show a water tank in the top room, an empty middle room, and a bottom room labeled BEDROOM, with a closet and tiny bathroom in one corner. Early correspondence confirms that this was more or less the original plan—a 1927 letter from then-president Walter S. Martin to the architects of the brand-new building asks why the heating system doesn’t extend up into the tower rooms, which were “intended to be used either as Rest Rooms for the faculty, or as quarters for the janitors or porters.” Maybe unsurprisingly, the answer was budget-related. The architects responded that “[t]he building was constructed under the Cost-plus plan and economy was apparently the watch word at the time. In the interest of economy this heating was left out entirely.” They then suggest an electric space heater (“The Majestic type is probably the best of the lot.”). For this or whatever reason, it seems that the tower wasn’t actually converted into living quarters until Morehouse worked on the project in the ’40s. Today you can still see evidence of the tower’s former life as a residence, with pipes that once were used for plumbing poking up through the floor and a mirrored cabinet mounted on a wall where a sink would have been.

3 Gail Sullivan, “How About a Ghost Story?,” San Francisco Sunday Examiner & Chronicle, January 9, 1972.

4 Ibid.

5 “Art Institute Puts Ghost to Work,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 30, 1976.

6 “A Ghost of Legend Haunts the Artists,” San Francisco Chronicle, October 31, 1968.

7 Bill Morehouse died in 1993. I have no idea what sort of unfinished business he may or may not have had in this life, but if given the option, I can think of one spot Bill might have chosen to haunt in a “mischievous but fundamentally benign” sort of way.

8 Myriam Weisang, “Hearts for Art’s Sake: A Profile of the San Francisco Art Institute and Its Second Annual Artists’ Valentines Exhibition/Auction,” San Francisco Bay Guardian, February 6, 1985.

9 This strange and terrible story crops up in Reflections from a Cinematic Cesspool, a very funny and wild sort of book written by the filmmaker George Kuchar, who taught at SFAI for forty years, up until 2011, the year of his death. George always taught in Studio 8, and the films his classes put together over the course of the semester were invariably awash in wigs and disguises and weird makeup and jury-rigged sets. George came into the studio to set up for class and saw what he took to be a dummy dressed up in clothes from the prop closet hanging from the lighting grid. He was so used to that kind of thing that it took him a while to realize that it wasn’t.

10 Rebecca LaFontaine-Larivee, “Richard’s Coat: Remembering Richard Irwin,” Empty Mirror, https://www.emptymirrorbooks.com/personal-essay/richards-coat(accessed April 10, 2019).