Casper Banjo: Serve the People

Author

Nina Zurier

Decade

1960s 1970s 2000s

Tags

Activism Community

Racial Justice

Printmaking Clothing

“Serve the People” is a Maoist slogan dating from 1944. It was adopted by the Black Panther Party, which was founded in Oakland, California, in 1966. One of the initial core practices of the BPP was armed citizen patrols to challenge Oakland police brutality. A second core practice was the establishment of the Free Breakfast for School Children Program in January 1969 at St. Augustine Church in Oakland; by the end of the year over ten thousand children a day were being fed across the United States. Federal authorities, threatened by the success of the program, attempted to shut it down through harassment, including raids while children were eating. Released from prison in 1970, Black Panther founder and minister of defense Huey P. Newton renewed focus on the breakfast program as a key mission of the Panthers. Today the People’s Breakfast Oakland continues the project, and sales of SFAI alumnus Stanley Greene’s photograph F*ck the Klan contribute to the program through his foundation, NOOR.

Casper Banjo studied printmaking at SFAI in the late 1960s and early 1970s, working with Patty Benson, Michi Itami, Richard Graf, and Kathan Brown. He received his BFA and MFA degrees, and was still paying off his student loans when he was killed by Oakland police in 2008 at the age of seventy.

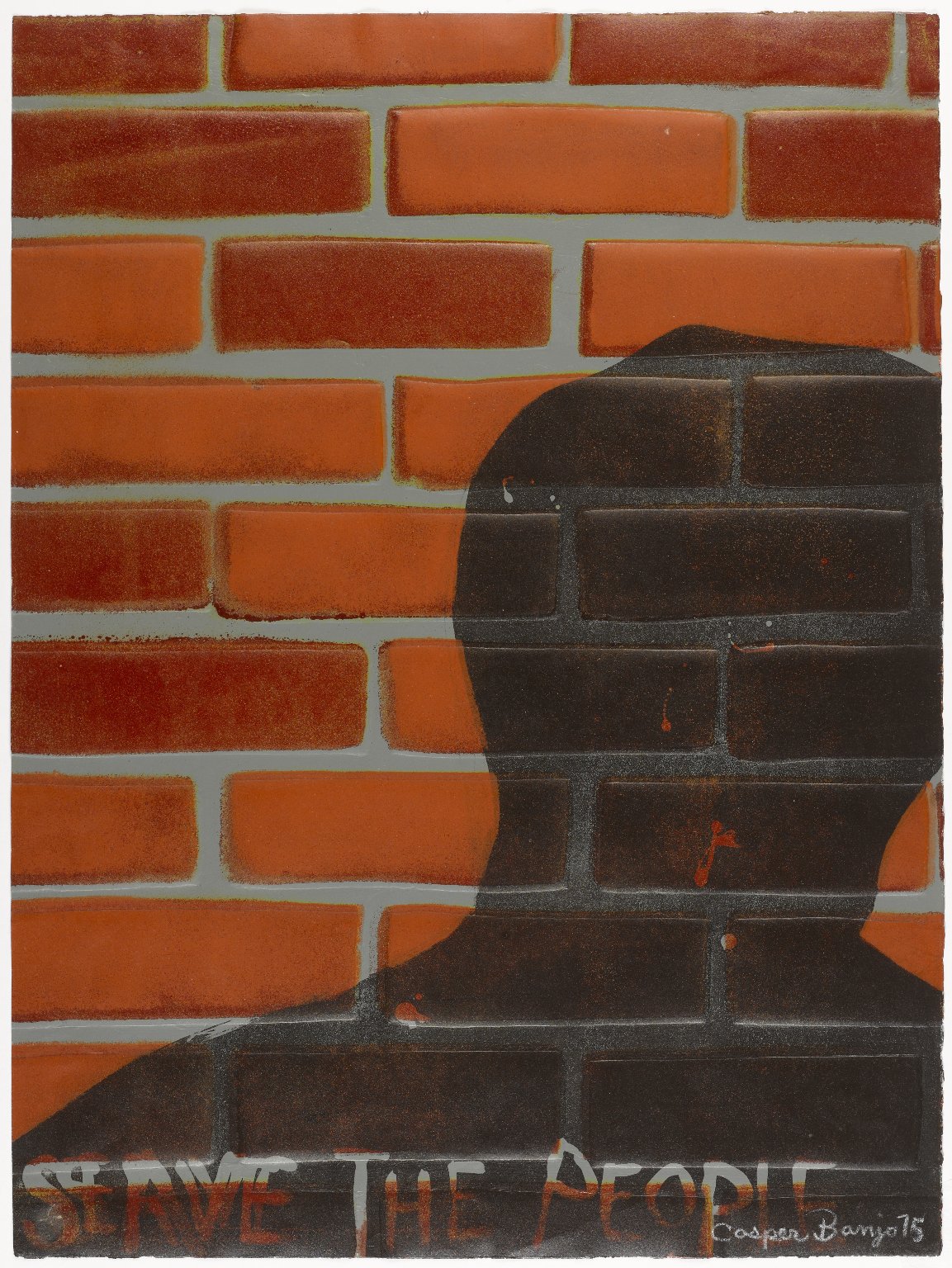

![Casper Banjo: Serve the People, 1975; mixed media on embossed paper; sheet: 29 1/2 × 22 in.; Brooklyn Museum, gift of R. M. Atwater, Anna Wolfrom Dove, Alice Fiebiger, Joseph Fiebiger, Belle Campbell Harriss, and Emma L. Hyde, by exchange, Designated Purchase Fund, Mary Smith Dorward Fund, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Carll H. de Silver Fund, 2012.80.5. © Casper Banjo estate.]()

The brick background seen in this print was a signature element of his work. According to Art Hazelwood, SFAI faculty member and longtime friend of Banjo, the obsession with bricks is

From the beginning of the Black Arts Movement in 1967, Black artists played a major role in educating their communities, through art, about African American history and the historic contributions made by African Americans to culture and society. Banjo was active in many organizations, including the Oakland Bay Area Black Artists (BABA) Collective, ProArts, the Art of Living Black, the California Society of Printmakers, and the National Minorities with Disabilities Coalition. He taught art to people with disabilities, children, single mothers, and the homeless in community art programs such as Nurturing Independence Through Artistic Development (NIAD) and the Center for Visual Arts. Banjo also contributed drawings to the homeless community’s newspaper Street Sheet, and worked on the annual art auctions for the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness.

Casper Banjo studied printmaking at SFAI in the late 1960s and early 1970s, working with Patty Benson, Michi Itami, Richard Graf, and Kathan Brown. He received his BFA and MFA degrees, and was still paying off his student loans when he was killed by Oakland police in 2008 at the age of seventy.

The brick background seen in this print was a signature element of his work. According to Art Hazelwood, SFAI faculty member and longtime friend of Banjo, the obsession with bricks is

“the key to understanding both Casper’s art and his life. The drama of his work and his life is the brick wall. The wall of bricks represents Casper the immovable, singular in vision and determination. It represents Casper the stoic philosopher, unmoved by passing fancies, and willing to point out injustice where he saw it.

“And Casper’s brick wall was visionary. He took the most concrete of forms, a form that met him at his earliest childhood; the brick wall in Memphis, in St. Louis and in Oakland. He saw brick walls everywhere. And Casper, through his art, slowly and with determination went through that brick wall. He created a visual language of transcendence through that brick wall. The great wall, the great barrier, that Casper felt profoundly was a personal wall, but it was also an historical wall and a social wall. It was the wall of racism. It was the wall of prejudice against disability. It was the wall of personal relations. And ultimately, it was the wall of mortality.”

—from Art Hazelwood, “Casper Banjo (1937–2008): An Appreciation,” Oakland Wiki

From the beginning of the Black Arts Movement in 1967, Black artists played a major role in educating their communities, through art, about African American history and the historic contributions made by African Americans to culture and society. Banjo was active in many organizations, including the Oakland Bay Area Black Artists (BABA) Collective, ProArts, the Art of Living Black, the California Society of Printmakers, and the National Minorities with Disabilities Coalition. He taught art to people with disabilities, children, single mothers, and the homeless in community art programs such as Nurturing Independence Through Artistic Development (NIAD) and the Center for Visual Arts. Banjo also contributed drawings to the homeless community’s newspaper Street Sheet, and worked on the annual art auctions for the San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness.

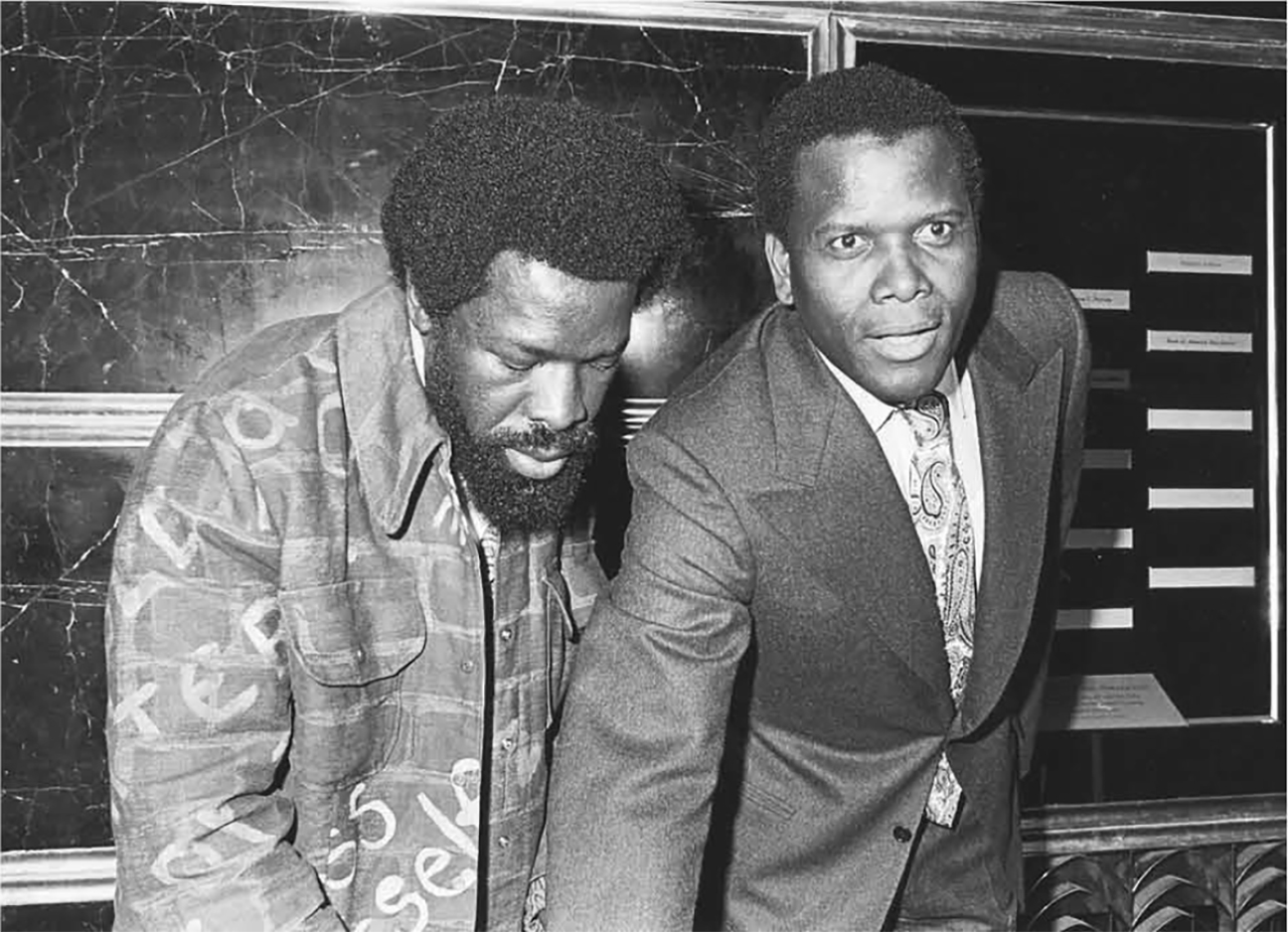

He was a member of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, Inc. (BFHFI), which began in Oakland in 1974. Banjo created the BFHFI’s version of the “Hollywood Walk of Fame,” overseeing the making of handprints from Harry Belafonte, Eartha Kitt, Sammy Davis Jr., Lena Horne, Sidney Poitier, and many others. By 1991, Black filmmaking had gained wide recognition, and the third annual TV broadcast of the Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame awards ceremony featured rapper M. C. Hammer, actress Robin Givens, and actor/director Mario Van Peebles as hosts for the two-hour special.

Banjo’s work was included in two major museum exhibitions during his lifetime—Impressions/Expressions: Black American Graphics, organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem and circulated by the Smithsonian Institution (1979–81); and Aesthetics of Graffiti, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1978)—and in a traveling exhibition organized by Gong Gallery in Lagos, Nigeria, among others. In 2012 the Brooklyn Museum acquired a large group of works from the Black Arts Movement, among which were three works by Banjo. The Brooklyn Museum’s 2014 exhibition Revolution! Works from the Black Arts Movement included Banjo’s A Black and White Situation (1976).

KPFA’s Pushing Limits, interview by Safi wa Nairobi with Casper Banjo on disability and the arts, October 7, 2005 (starts at 19:52)

Banjo’s work was included in two major museum exhibitions during his lifetime—Impressions/Expressions: Black American Graphics, organized by the Studio Museum in Harlem and circulated by the Smithsonian Institution (1979–81); and Aesthetics of Graffiti, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art (1978)—and in a traveling exhibition organized by Gong Gallery in Lagos, Nigeria, among others. In 2012 the Brooklyn Museum acquired a large group of works from the Black Arts Movement, among which were three works by Banjo. The Brooklyn Museum’s 2014 exhibition Revolution! Works from the Black Arts Movement included Banjo’s A Black and White Situation (1976).

KPFA’s Pushing Limits, interview by Safi wa Nairobi with Casper Banjo on disability and the arts, October 7, 2005 (starts at 19:52)

Links

Art Hazelwood, “Casper Banjo (1937–2008): An Appreciation,” Oakland Wiki. A biography of Casper Banjo by fellow printmaker, activist, and SFAI faculty member Art Hazelwood.

Angela Woodall, “Family of slain man asks: ‘How did we get here?’,” East Bay Times, March 22, 2008

Revolution! Works from the Black Arts Movement exhibition, Brooklyn Museum, 2014

The Instagram page for People’s Breakfast Oakland community support organization

The Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame, Inc. (BFHFI) was founded in Oakland, California, in 1974, the collaborative effort of Roy Thomas, Afro-American Studies Department at UC Berkeley; Mary Perry Smith, co-chairperson of the Cultural and Ethnic Affairs Guild at the Oakland Museum; and Sonny Buxton of the San Francisco Bay Area station KGO-TV. Link is to the Mary Perry Smith Black Filmmakers Hall of Fame Archives Collection, Indiana University.

“The Berkeley Revolution.” This digital archive was created by UC Berkeley students under the supervision of Scott Saul, with the support of the university’s Digital Humanities and Global Urban Humanities initiatives.

Film of Huey P. Newton’s release from prison, KQED, August 5, 1970

Janelle Bitker, “Oakland’s Black Artists Make Space for Themselves,” East Bay Express, January 17, 2018. An article about Oakland artists responding to gentrification and the political climate, with the intention of preserving the local legacy of Black culture.

SFAI faculty Leila Weefur was among the organizers for Black Aesthetic presentations at BAMPFA, 2017

KPFA: Police Killings of People with Disabilities, including Casper Banjo, from May 2, 2008