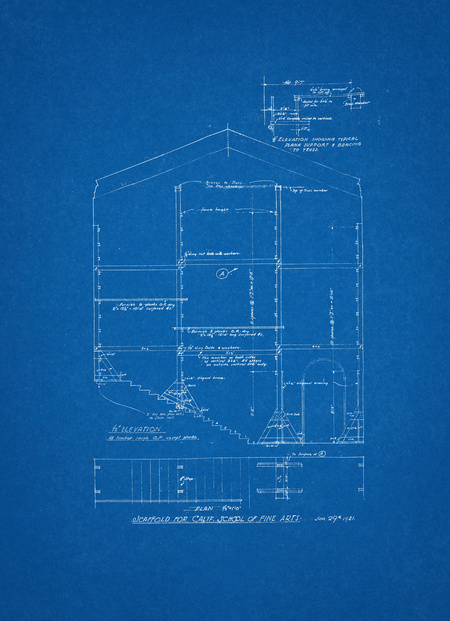

Studios 9 and 10 sit out back, tucked away in the shadow of SFAI’s main 1926 Arthur Brown–designed Chestnut Street building. They were part of Brown’s original plan but were finished a few years after everything else and have always maintained a sort of tacked-on quality—architecturally humble, hard to get to from almost everywhere else on campus, next to nothing but the parking lot. There are pros and cons to being a little provisional and out of the way. In this case, the cons seem mostly related to leaks and deferred maintenance. The pros are more ineffable, and have to do with freedom.

You can see it even in the early days, before the 1969 addition was built with its spacious sculpture studio. Back then, big messy sculpture projects happened out back in the spot where the parking lot is now, and for a while in the 1930s, when fresco painting was having a moment, Studio 9 was fitted with removable wall panels and students practiced mixing plaster and climbing up on ladders to paint them. It’s easy to imagine the beautiful mess of it—plaster and pigment dust all over, walls exploding with color and imagery that changed from week to week.

![]()

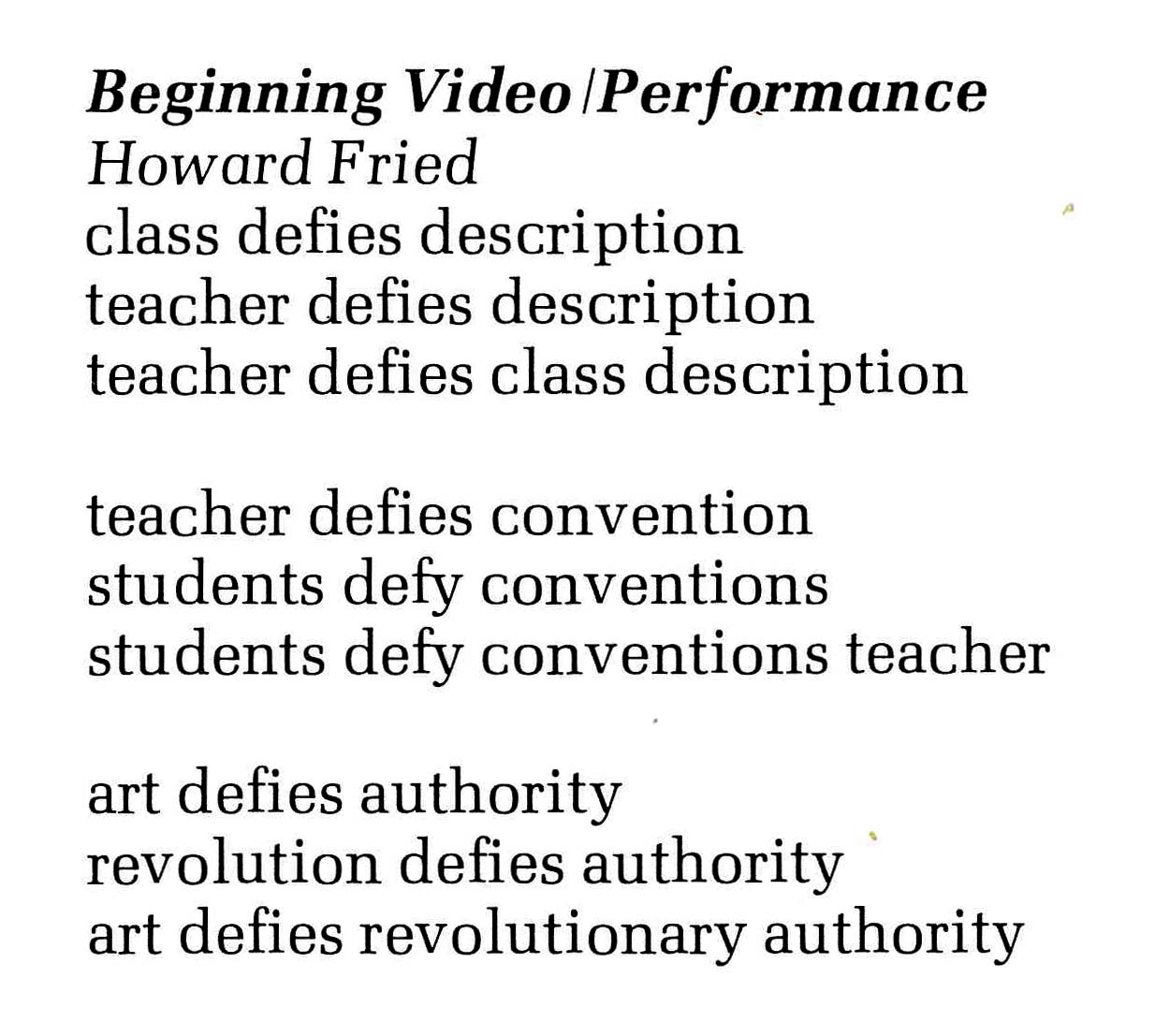

Even with all the extra space afforded by the 1969 building, even with the changing times, with conceptual and performance art taking hold, with the advent of consumer-grade video cameras, with the appearance of classes like Bruce Conner’s 1966 undergraduate seminar Wasted Time: Unproductive Activity of No Practical Application—even after all that, it was still difficult to carve out space for a Performance/Video Department at SFAI.

Tony Labat, a student at the time, was there for the whole thing. In a talk in 2016 with Howard Fried—who had championed the cause of the new department—Tony described tagging along to faculty senate meetings and documenting Howard’s efforts with a video camera “so that there would be no physical harm to him.”

You can see it even in the early days, before the 1969 addition was built with its spacious sculpture studio. Back then, big messy sculpture projects happened out back in the spot where the parking lot is now, and for a while in the 1930s, when fresco painting was having a moment, Studio 9 was fitted with removable wall panels and students practiced mixing plaster and climbing up on ladders to paint them. It’s easy to imagine the beautiful mess of it—plaster and pigment dust all over, walls exploding with color and imagery that changed from week to week.

Even with all the extra space afforded by the 1969 building, even with the changing times, with conceptual and performance art taking hold, with the advent of consumer-grade video cameras, with the appearance of classes like Bruce Conner’s 1966 undergraduate seminar Wasted Time: Unproductive Activity of No Practical Application—even after all that, it was still difficult to carve out space for a Performance/Video Department at SFAI.

Tony Labat, a student at the time, was there for the whole thing. In a talk in 2016 with Howard Fried—who had championed the cause of the new department—Tony described tagging along to faculty senate meetings and documenting Howard’s efforts with a video camera “so that there would be no physical harm to him.”

When the program was finally approved and funded, thanks to proceeds from the sale of SFAI’s set of Eadweard Muybridge photographs of Yosemite, Performance/Video was initially allocated one of the tiniest spaces on campus, a small, windowless room at the bottom of the ramp. It was, as Tony put it, a “godforsaken little room” right off the noisy sculpture area. Howard would close the door because of the noise, and it “really felt like a sort of psychiatric ward in there. It was incredibly claustrophobic.”

So when P/V managed to claim Studio 9 as its own, it was a real coup. Tony inaugurated the new space with a performance. This is how he describes it, looking back:

In other words, it’s the space, but it’s not just the space. It’s the holding of space that one person can do for another, the sustained attention, and the electricity in the room that sustained attention creates.

So when P/V managed to claim Studio 9 as its own, it was a real coup. Tony inaugurated the new space with a performance. This is how he describes it, looking back:

“It’s like what my mother and all the Cuban mothers that I grew up with did when you moved into a new space, which is that you bring the Yerba Buena, the mint, the cigar, the rum, and you do a despojo, you do a cleansing of the space. You get rid of all the past spirits and you start fresh, you start new.

I also of course really appreciate the image of Howard in the back, and how it was the first time I felt that no matter what I would do in that room, that he was giving me attention. It was just really an amazing thing to be there.”

In other words, it’s the space, but it’s not just the space. It’s the holding of space that one person can do for another, the sustained attention, and the electricity in the room that sustained attention creates.

Some of the P/V course listings from those early days, per Tony: Physical Education for Performance, Real Estate, Automechanics, Drugs 101, Sex for the Modern Mind, Principles of Latin Cuisine, Video Art and Health.

Some of the faculty who came through:

Vito Acconci, Dara Birnbaum, Valie Export, Karen Finley, Frank Gillette, Ingo Gunther, Tony Oursler, Moira Roth, Chris Burden, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Sharon Grace, Barbara Schmidt, and Doug Hall. Terry Fox, who—for his Adaline Kent Award exhibition—created a giant sound installation in the empty foundation of a demolished building downtown. Linda Montano, who told her life story while walking on a treadmill in front of the school for three hours; she sported a prom dress, dyed blue teeth, and a device that forced her mouth into a permanent smile. Darryl Sapien, who suspended himself thirty feet above the school’s meadow for eight hours, wrapped in blankets and plastic, hanging “like some kind of chrysalis undergoing a metamorphosis.” Bonnie Sherk, who ate her lunch in a cage at the Lion House of the San Francisco Zoo.

These links, by the way, are from SiteWorks: San Francisco Performance 1969–85, a project of University of Exeter professor Nick Kaye, who was so fascinated by a time and place four decades and a continent away that he decided to create this record of it. His is a project not only about what happened but about what “memories, traces and archival remains” are left to tell the story of what happened, what’s been forgotten, which photographs were thrown away or never taken in the first place, what locations have been transformed into something unrecognizable in an ever-changing city.

A decade after following Howard Fried around with a video camera in an attempt to avert violence at faculty senate meetings, Tony Labat was on the faculty, and Jennifer Locke was an undergraduate who had come to SFAI as a painting major, but found herself doing a performance as part of a freshman class that introduced students to the school’s various departments. She told me, “I did this really bad undergraduate performance, but it was so intense and powerful that it did something to me, and I actually had to go home. I skipped all the rest of my classes that day.” Later on, she took a class with Tony, and that changed everything:

Some of the faculty who came through:

Vito Acconci, Dara Birnbaum, Valie Export, Karen Finley, Frank Gillette, Ingo Gunther, Tony Oursler, Moira Roth, Chris Burden, Lynn Hershman Leeson, Sharon Grace, Barbara Schmidt, and Doug Hall. Terry Fox, who—for his Adaline Kent Award exhibition—created a giant sound installation in the empty foundation of a demolished building downtown. Linda Montano, who told her life story while walking on a treadmill in front of the school for three hours; she sported a prom dress, dyed blue teeth, and a device that forced her mouth into a permanent smile. Darryl Sapien, who suspended himself thirty feet above the school’s meadow for eight hours, wrapped in blankets and plastic, hanging “like some kind of chrysalis undergoing a metamorphosis.” Bonnie Sherk, who ate her lunch in a cage at the Lion House of the San Francisco Zoo.

These links, by the way, are from SiteWorks: San Francisco Performance 1969–85, a project of University of Exeter professor Nick Kaye, who was so fascinated by a time and place four decades and a continent away that he decided to create this record of it. His is a project not only about what happened but about what “memories, traces and archival remains” are left to tell the story of what happened, what’s been forgotten, which photographs were thrown away or never taken in the first place, what locations have been transformed into something unrecognizable in an ever-changing city.

A decade after following Howard Fried around with a video camera in an attempt to avert violence at faculty senate meetings, Tony Labat was on the faculty, and Jennifer Locke was an undergraduate who had come to SFAI as a painting major, but found herself doing a performance as part of a freshman class that introduced students to the school’s various departments. She told me, “I did this really bad undergraduate performance, but it was so intense and powerful that it did something to me, and I actually had to go home. I skipped all the rest of my classes that day.” Later on, she took a class with Tony, and that changed everything:

“It changed my whole paradigm, changing my sense of reality in a deep and profound way. It plunged me into the exact kind of experience that I had been looking for but hadn’t been able to locate yet—something transgressive and taboo, having to do with threshold spaces. The class was challenging, high intensity, and often thick with a sense of the uncanny. You could cut the tension in that room with a knife. It was sexy, dangerous, and exciting.”

In one performance, a student decapitated a chicken and swung it around over his head like a lasso, getting blood on everyone in the room. In another, a student who lived on a boat and slept in a coffin brought in the dead seal he had found washed up and played video of a brain surgery while performing card tricks with the carcass. Studios 9 and 10 offered the freedom to do all of this, to throw some chicken blood around if you wanted to, in a room full of people who were offering you the gift of their attention. According to Jennifer,

“Anything that happened in studios 9 and 10 stayed in studios 9 and 10. It felt like a secret society. It was behind the school–sort of like in the toilet/garage of the school, so there was a lot freedom. It totally changed my life. I had felt alone before that, and finally I’d found this tribe of people and this shared philosophy. SFAI has always drawn idiosyncratic, obsessed, unique individuals who maybe don’t fit in anywhere else. There’s a camaraderie, a community, often leading to lifelong relationships. I don’t know if there’s anywhere else quite like it.”

There’s a sense in which, in Studios 9 and 10, the assignment really is as simple as: decide what you will do within these walls. And you can take that assignment on, or you reject even its minimal constraints. Maybe, like longtime instructor Paul Kos, you climb the walls instead:

Or you leave the room all together, and then you leave the city and you go to the mountains to paint with watercolors.

Studios 9 and 10 are a clubhouse, or they’re a garage, or a toilet, or a secret society, or—as Kos wrote in his 2004 essay in the catalog for that year’s MFA exhibition—a “laboratory.” He knew it as well as anyone, so I’ll leave you with his essay, in full:

I like the way the British say it, “la BOR a tory.” And indeed, that it has been since 1978 (almost twenty-five years)—a laboratory, kitchen, clubhouse, den, bureau of weights and measures, assay office, saloon, playpen, Olympic site, barber and apothecary shop, tattoo parlor, prison, gulag, spa. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language calls any place, situation, set of conditions, or the like, conductive to experimentation, investigation, observation, etc., a laboratory. Underfunded, mildewed, isolated, cold, and damp, this small piece of SFAI real estate at one time, before the demise of the NEA, provided one quarter of all grantees for the entire United States in New Genres. Not bad for 625 square feet, proving the axiom that less is more. “You should be able to make art with what’s in your back pocket, even if it’s empty,” said a friend of mine, and Studio 10 has been a catalyst to every extreme imaginable. Indeed—Up, Down, Strange, and Charmed.

Naïve recruits and hardened veterans have measured the architecture as well as any medieval frank mason armed with plumb bob, level, and square. For instance, I know the floor is not level, a fact revealed when one, “he,” who shall remain unnamed, handcuffed himself behind his back, knelt on his skateboard, and began to swallow the twenty feet of ripped bed sheet that was tied to a defunct radiator on the opposite wall. After gagging and swallowing and gagging and swallowing and gagging and swallowing he reached the end of the tether, opened his mouth and gullet and suddenly the skateboard and he rolled backward to where they had commenced. It proved to be an uphill swallow.

How high politically and physical is the reach of Studio 10? Another “he” filled three very large balloons with helium and had us follow him to the ramparts of the school, where he released them. In three minutes, after they had ascended quite high, a nuclear submarine surfaced in the Bay between Alcatraz and our position, distinctly signaled him, and then slithered back into the depths. Both the artist and the submarine captain belonged to the secretive Masonic Order.

Studio 10 does not foster therapy but, by default, is therapeutic. In one such case, a shy one hid in the closet and niches and crannies during every single meeting, and the rest of us would look for him. So he got to be more and more clandestine, one time spending three hours in the locker below the TV monitor, and another time suspended in the skylight, and the last time seen only through a telescope waving to us from Alcatraz.

Another was exiled from Studio 10 for being rowdy and sent to an austere monastery in Spain for a month to learn discipline. Awakened for matins, lauds, complines, and vespers, the punk became a Gregorian.

She-power was witnessed when, dressed in an executive, three-piece, pinstriped, business suit, she baited us to follow her to THE marketplace—Market Street. Then on her belly, elbows, and knees, reptile-like, she crawled its entire length to the consternation and admiration of locals and tourists alike.

Another broke the ice socially. He literally installed two twenty-five-pound blocks of ice on two chairs in opposite corners of Studio 10. On one block of ice was a small cocktail olive. He proceeded to drop his drawers, scoot across the floor with his pants at his ankles, and with his naked ass mounted the block of ice with the olive. Squirming around, he then got off, scooted back across the room, mounted the other block, and—Voila!—invisibly deposited the olive, using his hands only to pull his pants back up.

Occasionally the bittersweet of real life slips in under the door, and this time it was in the form of a requiem. When she died of an accident the morgue needed someone to identify the body, and since she had been here only a few weeks, no one in the administration knew what she looked like. So our group went out as her surrogate family to identify her remains. A short time later, her parents moved out from New Jersey to finish her semester. This couple witnessed countless eulogies in the form of video, performance, and installation for the remaining ten weeks. At the end they hugged us and went home happy—their daughter had fulfilled her aspirations.

There is no hierarchy or exclusivity of medium in Studio 10. “Thinking on one’s feet” is the only craft taught within its walls. Some seventy-five hundred artists have spawned their ideas there, and some of the best paintings, photos, and sculptures I’ve ever seen, anywhere, without qualifications, were installed there, as well as the more expected performance and video pieces. If “Put your money where your mouth is” is a truism, then the twenty-four years of discourse under the auspices of tuition fees has been money well spent.

Studio 10 is arrogant and pompous. And humble and unassuming. It is brusque, brazen, and alive, welcoming and scary, but it is always . . . (hold your head up kind of snootily, and exaggerate) . . . a la BOR a tory.

BA

Studios 9 and 10 are a clubhouse, or they’re a garage, or a toilet, or a secret society, or—as Kos wrote in his 2004 essay in the catalog for that year’s MFA exhibition—a “laboratory.” He knew it as well as anyone, so I’ll leave you with his essay, in full:

I like the way the British say it, “la BOR a tory.” And indeed, that it has been since 1978 (almost twenty-five years)—a laboratory, kitchen, clubhouse, den, bureau of weights and measures, assay office, saloon, playpen, Olympic site, barber and apothecary shop, tattoo parlor, prison, gulag, spa. The Random House Dictionary of the English Language calls any place, situation, set of conditions, or the like, conductive to experimentation, investigation, observation, etc., a laboratory. Underfunded, mildewed, isolated, cold, and damp, this small piece of SFAI real estate at one time, before the demise of the NEA, provided one quarter of all grantees for the entire United States in New Genres. Not bad for 625 square feet, proving the axiom that less is more. “You should be able to make art with what’s in your back pocket, even if it’s empty,” said a friend of mine, and Studio 10 has been a catalyst to every extreme imaginable. Indeed—Up, Down, Strange, and Charmed.

Naïve recruits and hardened veterans have measured the architecture as well as any medieval frank mason armed with plumb bob, level, and square. For instance, I know the floor is not level, a fact revealed when one, “he,” who shall remain unnamed, handcuffed himself behind his back, knelt on his skateboard, and began to swallow the twenty feet of ripped bed sheet that was tied to a defunct radiator on the opposite wall. After gagging and swallowing and gagging and swallowing and gagging and swallowing he reached the end of the tether, opened his mouth and gullet and suddenly the skateboard and he rolled backward to where they had commenced. It proved to be an uphill swallow.

How high politically and physical is the reach of Studio 10? Another “he” filled three very large balloons with helium and had us follow him to the ramparts of the school, where he released them. In three minutes, after they had ascended quite high, a nuclear submarine surfaced in the Bay between Alcatraz and our position, distinctly signaled him, and then slithered back into the depths. Both the artist and the submarine captain belonged to the secretive Masonic Order.

Studio 10 does not foster therapy but, by default, is therapeutic. In one such case, a shy one hid in the closet and niches and crannies during every single meeting, and the rest of us would look for him. So he got to be more and more clandestine, one time spending three hours in the locker below the TV monitor, and another time suspended in the skylight, and the last time seen only through a telescope waving to us from Alcatraz.

Another was exiled from Studio 10 for being rowdy and sent to an austere monastery in Spain for a month to learn discipline. Awakened for matins, lauds, complines, and vespers, the punk became a Gregorian.

She-power was witnessed when, dressed in an executive, three-piece, pinstriped, business suit, she baited us to follow her to THE marketplace—Market Street. Then on her belly, elbows, and knees, reptile-like, she crawled its entire length to the consternation and admiration of locals and tourists alike.

Another broke the ice socially. He literally installed two twenty-five-pound blocks of ice on two chairs in opposite corners of Studio 10. On one block of ice was a small cocktail olive. He proceeded to drop his drawers, scoot across the floor with his pants at his ankles, and with his naked ass mounted the block of ice with the olive. Squirming around, he then got off, scooted back across the room, mounted the other block, and—Voila!—invisibly deposited the olive, using his hands only to pull his pants back up.

Occasionally the bittersweet of real life slips in under the door, and this time it was in the form of a requiem. When she died of an accident the morgue needed someone to identify the body, and since she had been here only a few weeks, no one in the administration knew what she looked like. So our group went out as her surrogate family to identify her remains. A short time later, her parents moved out from New Jersey to finish her semester. This couple witnessed countless eulogies in the form of video, performance, and installation for the remaining ten weeks. At the end they hugged us and went home happy—their daughter had fulfilled her aspirations.

There is no hierarchy or exclusivity of medium in Studio 10. “Thinking on one’s feet” is the only craft taught within its walls. Some seventy-five hundred artists have spawned their ideas there, and some of the best paintings, photos, and sculptures I’ve ever seen, anywhere, without qualifications, were installed there, as well as the more expected performance and video pieces. If “Put your money where your mouth is” is a truism, then the twenty-four years of discourse under the auspices of tuition fees has been money well spent.

Studio 10 is arrogant and pompous. And humble and unassuming. It is brusque, brazen, and alive, welcoming and scary, but it is always . . . (hold your head up kind of snootily, and exaggerate) . . . a la BOR a tory.

BA